Explanatory Memorandum

(Circulated by authority of the Treasurer, the Hon Jim Chalmers MP)Attachment 1: Impact Analysis - Strengthening Australia's Financial Market Infrastructure regulatory framework

Financial Market Infrastructure Regulatory Reforms, 2020 Advice to Government from the Council of Financial Regulators

Executive Summary

Introduction

Financial market infrastructures (FMIs) are the key entities that enable, facilitate and support trading in Australia's capital markets. FMIs include financial market operators, benchmark administrators, clearing and settlement facilities and derivative trade repositories. The financial system's reliance upon FMIs, particularly central counterparties (CCPs), has increased significantly following the 2008 crisis as a result of reforms intended to reduce systemic risk. Today, FMIs in Australia support transactions in securities with a total annual value of $18 trillion and derivatives with a total annual notional value of $185 trillion. A disruption to the orderly provision of FMI services could cause a disruption to the wider financial system, which may have large economic costs.

FMIs face a wide variety of risks. The 2008 crisis illustrated the financial and counterparty risks to which financial institutions, including FMIs, are exposed, and the importance of sound risk management to address these risks. More recently, the operational disruption and market volatility associated with the economic fallout from the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has highlighted the potential for an unforeseen event to impact the smooth functioning of FMIs. In the most extreme cases, these risks could threaten the viability of these critical infrastructures.

As the regulators of FMIs, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) (together, the Regulators) need strong and dependable powers to carry out their mandates and mitigate the risk of disruption to FMI services. The Regulators currently have a range of powers with respect to FMIs. However, the options available to the Regulators to address the potential insolvency of an FMI or other severe threats to its continued operation are very limited. The proposed reforms are also needed to improve the ability of the Regulators to manage such risks ahead of any potential crises, by enhancing the day- to-day regulatory regime and introducing powers to prepare for the orderly resolution of a clearing and settlement facility. In addition, the current distribution of regulatory powers does not always reflect the responsibilities of each Regulator, and the legislation provides a number of operational powers to the Minister (which are currently delegated to ASIC).

The Council of Financial Regulators (CFR) considers that the limitations of the current framework, combined with the current heightened global risk environment and the growing systemic importance of FMIs, means that reforms to existing powers – as well as some additional powers to manage the risks associated with FMIs and promote reliability and integrity of the markets that FMIs support – are required. This has been acknowledged in a number of independent reviews including the 2014 Financial System Inquiry and the International Monetary Fund's (IMF's) 2019 Financial System Assessment Program review.

Recommendations

This advice to Government sets out the CFR's case for reform and makes 16 recommendations for regulatory reform that are intended to:

- •

- introduce a resolution regime for licensed clearing and settlement facilities;

- •

- strengthen the Regulators' supervisory and enforcement powers in relation to FMIs; and

- •

- redistribute existing powers between ASIC, the RBA and the Minister to make the regulatory process more efficient and to better distinguish between operational and strategic functions.

The recommendations outlined in this advice were broadly supported by stakeholders in the recent public consultation (conducted between November 2019 and March 2020). In some cases, the recommendations have been refined to address the feedback provided during that consultation.

Should the Government proceed with the reforms, stakeholders will have the opportunity to engage further with the proposed reforms at a later stage in the process, once draft legislation to enact the reforms has been released publicly.

Financial Market Infrastructure Regulatory Reforms, 2019 Consultation Paper, Council of Financial Regulators

Executive Summary

The term financial market infrastructures (FMIs) refers to institutions that perform fundamental activities in financial markets. They include operators of financial markets, benchmark administrators, clearing and settlement facilities and derivatives trade repositories. FMIs are critical to the smooth and efficient functioning of the financial system. FMIs licensed in Australia support transactions in securities with a total annual value of $16 trillion and derivatives with a total annual value of $150 trillion. These markets turn over value equivalent to Australia's annual GDP every three business days. Securities and derivatives are used by investors and businesses in order to raise capital and finance, borrow and lend funds, invest in equities and debt securities and manage the risks associated with their activities. Investors rely on FMIs for access to transparent prices and a safe means of transacting in their investments, which include over $640 billion in superannuation assets held in Australian equities and fixed income assets. A disruption to the services provided by FMIs could have very severe consequences for the Australian financial system and to the investors and businesses that rely on FMIs.

International reforms following the 2008 financial crisis have increased both the role of FMIs in the financial system and the risks they face. Clearing and settlement facilities in particular are now critically important due to increased central clearing of over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives. OTC derivatives are widely utilised by financial institutions to manage their exposure to risk and there are now around $60 trillion (notional value) of Australian OTC derivative contracts outstanding, with a significant proportion of these centrally cleared.

This paper sets out the Council of Financial Regulator's (CFR's) proposed reforms to the regulation of FMIs. The reforms aim to ensure the effective regulation of the systems, services and facilities that underpin Australia's financial system.

The package includes changes to the licensing and supervision frameworks for financial market operators, benchmark administrators, clearing and settlement facilities and derivatives trade repositories, and a new crisis management regime for clearing and settlement facilities. These proposals aim to provide the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) (the Regulators) with strong and effective powers to continue to fulfil their regulatory responsibilities.

The proposed reforms will address the recommendations of several reviews of Australia's financial system, which concluded that the current regulatory regime for FMIs should be enhanced to increase its effectiveness and align to international best practice. These reviews include the 2014 Financial System Inquiry, the 2019 International Monetary Fund (IMF) Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP) and previous work by the CFR. The reforms build on recent improvements to the regulation of authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) and insurers and will help ensure the Australian economy is supported by a strong, well-functioning financial system.

This paper includes both new proposals and proposals that were the subject of previous consultation undertaken by the CFR. The CFR is primarily concerned with stakeholder feedback on new or changed reform proposals, but existing proposals are included in this paper to provide a complete picture of the proposed regulatory reform package.

Chapter 1 of this paper provides the rationale for reform and a brief overview of the current regulatory arrangements and the powers and functions of each of the Minister, ASIC and the RBA under the current legislation.

Chapter 2 outlines proposals designed to make sure the licensing regimes for relevant entities will be fit for purpose and effective into the future. The CFR proposes to change the roles of the Regulators so that operational licensing and related decisions sit with the Regulators and not the Minister. The Minister would retain powers in relation to strategic matters. This chapter also includes proposals to clarify when operators need to be licensed, and place additional responsibilities and obligations on licensees, reflecting their importance to the Australian financial system.

Chapter 3 outlines a number of proposals to enhance the supervisory powers of the Regulators. This includes enhancements to directions powers and information-gathering powers, a new rule-making power for ASIC, new arrangements in relation to changes in control of licensees, and the introduction of a fit and proper regime for key decision-makers.

Chapter 4 proposes the introduction of a resolution regime for clearing and settlement facilities, concentrating on modifications to proposals set out in an earlier consultation on this regime. Key proposals include expanding the scope of certain resolution powers to allow the resolution authority to take action in respect of related bodies corporate of a clearing and settlement facility licensee (CSFL) in resolution, and introducing resolution planning and resolvability powers. The CFR does not propose that the resolution regime will cover trade repositories at this time.

2014 Financial System Inquiry Report

Executive summary

This report responds to the objective in the Inquiry's Terms of Reference to best position Australia's financial system to meet Australia's evolving needs and support economic growth. It offers a blueprint for an efficient and resilient financial system over the next 10 to 20 years, characterised by the fair treatment of users.

The Inquiry has made 44 recommendations relating to the Australian financial system. These recommendations reflect the Inquiry's judgement and are based on evidence received by the Inquiry. The Inquiry's test has been one of public interest: the interests of individuals, businesses, the economy, taxpayers and Government.

Australia's financial system has performed well since the Wallis Inquiry and has many strong characteristics. It also has a number of weaknesses: taxation and regulatory settings distort the flow of funding to the real economy; it remains susceptible to financial shocks; superannuation is not delivering retirement incomes efficiently; unfair consumer outcomes remain prevalent; and policy settings do not focus on the benefits of competition and innovation. As a result, the system is prone to calls for more regulation.

To put these issues in context, the Overview first deals with the characteristics of Australia's economy. It then describes the characteristics of and prerequisites for a well-functioning financial system and the Inquiry's philosophy of financial regulation.

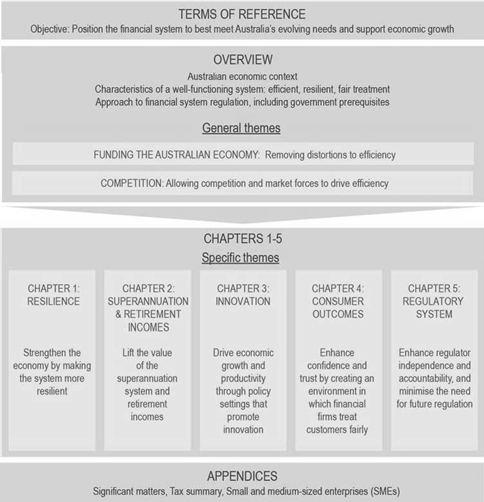

The Inquiry focuses on seven themes in this report (summarised in Guide to the Financial System Inquiry Final Report). The Overview deals with the general themes of funding the Australian economy and competition.

The Inquiry has also made recommendations on five specific themes, which comprise the next chapters of this report:

- •

- Strengthen the economy by making the financial system more resilient.

- •

- Lift the value of the superannuation system and retirement incomes.

- •

- Drive economic growth and productivity through settings that promote innovation.

- •

- Enhance confidence and trust by creating an environment in which financial firms treat customers fairly.

- •

- Enhance regulator independence and accountability, and minimise the need for future regulation.

These recommendations seek to improve efficiency, resilience and fair treatment in the Australian financial system, allowing it to achieve its potential in supporting economic growth and enhancing standards of living for current and future generations.

Guide to the Financial System Inquiry Final Report

Overview and general themes

The Inquiry has taken into account important features of Australia's economy. Australia has an open, market-based economy and is a net importer of capital. The Australian economy faces a considerable productivity challenge, and the Australian population, like many around the world, is ageing. Finally, Australia is in the midst of one of the most ubiquitous, generally applicable technology changes the world has ever seen.

Characteristics of an effective financial system

The financial sector plays a vital role in supporting a vibrant, growing economy that improves the standard of living for all Australians. The system's ultimate purpose is to facilitate sustainable growth in the economy by meeting the financial needs of its users. The Inquiry believes the financial system will achieve this goal if it operates in a manner that is:

- •

- Efficient: An efficient system allocates Australia's scarce financial and other resources for the greatest possible benefit to our economy, supporting growth, productivity and prosperity.

- •

- Resilient: The financial system should adjust to changing circumstances while continuing to provide its core economic functions, even during severe shocks. Institutions in distress should be resolvable with minimal costs to depositors, policy holders, taxpayers and the real economy.

- •

- Fair: Fair treatment occurs where participants act with integrity, honesty, transparency and non-discrimination. A market economy operates more effectively where participants enter into transactions with confidence they will be treated fairly.

Confidence and trust in the system are essential ingredients in building an efficient, resilient and fair financial system that facilitates economic growth and meets the financial needs of Australians. The Inquiry considers that all financial system participants have roles and responsibilities in engendering that confidence and trust.

The Inquiry's approach to financial system regulation

Central to the Inquiry's philosophy is the principle that the financial system should be subject and responsive to market forces, including competition.

However, competitive markets need to operate within a strong and effective legal and policy framework provided by Government. This includes predictable rule of law with strong property rights; a freely convertible floating currency and free flow of trade, investment and capital across borders; a strong fiscal position; a sound and independent monetary policy framework; and an effective, accountable and transparent government.

The Inquiry's approach to policy intervention is guided by the public interest. Given the inevitable trade-offs involved, deciding how and when policy makers should intervene in the financial system requires considerable judgement. Intervention should seek to balance efficiency, resilience and fairness in a way that builds participants' confidence and trust. Intervention should only occur where its benefits to the economy as a whole outweigh its costs, and should always seek to be proportionate and cost sensitive.

General themes

The Inquiry identified two general themes where there is significant scope to improve the functioning of the financial system:

- 1.

- Funding the Australian economy.

- 2.

- Competition.

Funding the Australian economy

The core function of the Australian financial system is to facilitate the funding of sustainable economic growth and enhance productivity in the Australian economy. The Inquiry believes Government's role in funding markets should generally be neutral regarding the channel, direction, source and size of the flow of funds.

The Inquiry identified a number of distortions that impede the efficient market allocation of financial resources, including taxation, information imbalances and unnecessary regulation. Reducing the distortionary effects of taxation should lead the system to allocate savings (including foreign savings) more efficiently and price risk more accurately. The Inquiry has referred the identified tax issues for consideration in the Tax White Paper.

A number of the Inquiry's recommendations aim to assist small and medium-sized enterprises in obtaining better access to funding. To strengthen Australia's ability to continue to access funding, both domestically and from offshore sources, recommendations have been made to improve the resilience of the Australian financial system. More broadly, given that Australia's growing superannuation system will have an increasing influence on future funding flows, the Inquiry believes that the recommendations it has made to improve the efficiency of the superannuation system would also enhance financial system funding efficiency.

Competition

Competition and competitive markets are at the heart of the Inquiry's philosophy for the financial system. The Inquiry sees them as the primary means of supporting the system's efficiency. Although the Inquiry considers competition is generally adequate, the high concentration and increasing vertical integration in some parts of the Australian financial system has the potential to limit the benefits of competition in the future and should be proactively monitored over time.

The Inquiry's approach to encouraging competition is to seek to remove impediments to its development. The Inquiry has made recommendations to amend the regulatory system, including: narrowing the differences in risk weights in mortgage lending; considering a competitive mechanism to allocate members to more efficient superannuation funds; and ensuring regulators are more sensitive to the effects of their decisions on competition, international competitiveness and the free flow of capital.

In particular, the state of competition in the financial system should be reviewed every three years, including assessing changes in barriers to international competition.

Recommendations relating to funding and competition are listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Funding the Australian economy and competition recommendations

| Funding the Australian economy | |

| Number | Description |

| – Tax observations | |

| 18 | Crowdfunding |

| 19 | Data access and use |

| 20 | Comprehensive credit reporting |

| 33 | Retail corporate bond market |

| Competition | |

| Number | Description |

| 2 | Narrow mortgage risk weight differences |

| 10 | Improving efficiency during accumulation |

| 14 | Collaboration to enable innovation |

| 15 | Digital identity |

| 16 | Clearer graduated payments regulation |

| 18 | Crowdfunding |

| 19 | Data access and use |

| 20 | Comprehensive credit reporting |

| 27 | Regulator accountability |

| 30 | Strengthening the focus on competition in the financial system |

| 39 | Technology neutrality |

| 42 | Managed investment scheme regulation |

Chapter 1: Resilience

Historically, Australia has maintained a strong and stable financial system supported by effective stability settings. However, the Australian financial system has characteristics that give rise to particular risks, including its high interconnectivity domestically and with the rest of the world, and its dependence on importing capital. More can be done to strengthen the resilience of Australia's financial system to avoid or limit the costs of future financial crises, which can deeply damage an economy and have lasting effects on people's lives.

As the banking sector is at the core of the Australian financial system, its safety is of paramount importance. Australia should aim to have financial institutions with the strength to not only withstand plausible shocks but to continue to provide critical economic functions, such as credit and payment services, in the face of these shocks. Adhering to international regulatory norms will help ensure Australian financial institutions and markets are not disadvantaged in raising funds in international financial markets.

The Inquiry's recommendations to improve resilience aim to:

- •

- Strengthen policy settings that lower the probability of failure, including setting Australian bank capital ratios such that they are unquestionably strong by being in the top quartile of internationally active banks.

- •

- Reduce the costs of failure, including by ensuring authorised deposit-taking institutions maintain sufficient loss absorbing and recapitalisation capacity to allow effective resolution with limited risk to taxpayer funds — in line with international practice.

These recommendations seek to ensure that Australia's financial system remains resilient into the future, and that it continues to provide its core economic functions, even in times of financial stress. These recommendations should also produce efficiency benefits, including through reducing implicit guarantees and volatility in the economy and promoting confidence and trust.

Chapter 2: Superannuation and retirement incomes

Australia's superannuation system is large by international standards and has grown rapidly since the Wallis Inquiry, primarily as a result of Government policy settings.

An efficient superannuation system is critical to help Australia meet the economic and fiscal challenges of an ageing population. The system has considerable strengths. It plays an important role in providing long-term funding for economic activity in Australia both directly and indirectly through funding financial institutions, and it contributed to the stability of the financial system and the economy during the global financial crisis.

However, the superannuation system is not operationally efficient due to a lack of strong price-based competition. Superannuation assets are not being efficiently converted into retirement incomes due to a lack of risk pooling and over-reliance on individual account-based pensions.

The Inquiry's recommendations to strengthen the superannuation system aim to:

- •

- Set a clear objective for the superannuation system to provide income in retirement.

- •

- Improve long-term net returns for members by introducing a formal competitive process to allocate new workforce entrants to high-performing superannuation funds, unless the Stronger Super reforms prove effective.

- •

- Meet the needs of retirees better by requiring superannuation trustees to pre-select a comprehensive income product in retirement for members to receive their benefits, unless members choose to take their benefits in another way.

These recommendations seek to improve the outcomes for superannuation fund members and help Australia to manage the challenges of an ageing population.

Chapter 3: Innovation

Technology-driven innovation is transforming the financial system, as evidenced by the emergence of new business models and products, and substantial investment in areas such as mobile banking, cloud computing and payment services.

Although innovation has the potential to deliver significant efficiency benefits and improve system outcomes, it also brings risks. Consumers, businesses and government can be adversely affected by new developments, which may also challenge regulatory frameworks and regulators' ability to respond.

The Inquiry believes the innovative potential of Australia's financial system and broader economy can be supported by taking action to ensure policy settings facilitate future innovation that benefits consumers, businesses and government.

The Inquiry's recommendations to facilitate innovation aim to:

- •

- Encourage industry and government to work together to identify innovation opportunities and emerging network benefits where government may need to facilitate industry coordination and action.

- •

- Strengthen Australia's digital identity framework through the development of a national strategy for a federated-style model of trusted digital identities.

- •

- Remove unnecessary regulatory impediments to innovation, particularly in the payments system and in fundraising for small businesses.

- •

- Enable the development of data-driven business models through holding a Productivity Commission Inquiry into the costs and benefits of increasing access to and improving the use of private and public sector data.

These recommendations will contribute to developing a dynamic, competitive, growth-oriented and forward-looking financial system for Australia.

Chapter 4: Consumer outcomes

Fundamental to fair treatment is the concept that financial products and services should perform in the way that consumers expect or are led to believe.

The current framework is not sufficient to deliver fair treatment to consumers. The most significant problems relate to shortcomings in disclosure and financial advice, which means some consumers are sold financial products that are not suited to their needs and circumstances. Although the regime should not be expected to prevent all consumer losses, self-regulatory and regulatory changes are needed to strengthen financial firms' accountability.

The Inquiry's recommendations to improve consumer outcomes aim to:

- •

- Improve the design and distribution of financial products through strengthening product issuer and distributor accountability, and through implementing a new temporary product intervention power for the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC).

- •

- Further align the interests of firms and consumers, and improve standards of financial advice, by lifting competency and increasing transparency regarding financial advice.

- •

- Empower consumers by encouraging industry to harness technology and develop more innovative and useful forms of disclosure.

These recommendations seek to strengthen the current framework to promote consumer trust in the system and fair treatment of consumers.

Chapter 5: Regulatory system

Australia needs strong, independent and accountable regulators to help maintain confidence and trust in the financial system, thereby attracting investment and supporting growth. This requires proactive regulators with the right skills, culture, powers and funding.

Australia's regulatory architecture does not need major change; however, the Inquiry has made recommendations to improve the current arrangements. Government currently lacks a regular process that allows it to assess the overall performance of financial regulators. Regulators' funding arrangements and enforcement tools have some significant weaknesses, particularly in the case of ASIC. In addition, it is not clear whether adequate consideration is currently given to competition and efficiency in designing and applying regulation.

The Inquiry's recommendations to refine Australia's regulatory system and keep it fit for purpose aim to:

- •

- Improve the accountability framework governing Australia's financial sector regulators by establishing a new Financial Regulator Assessment Board to review their performance annually.

- •

- Ensure Australia's regulators have the funding, skills and regulatory tools to deliver their mandates effectively.

- •

- Rebalance the regulatory focus towards competition by including an explicit requirement to consider competition in ASIC's mandate and conduct three-yearly external reviews of the state of competition.

- •

- Improve the process for implementing new financial regulations.

These recommendations seek to make Australia's financial regulators more effective, adaptable and accountable.

Appendix 1: Significant matters

In addition to the recommendations in the above areas, the Inquiry has made 13 recommendations relating to other significant matters. These are contained in Appendix 1: Significant matters.

Appendix 2: Tax summary

A number of tax observations are included in Appendix 2: Tax summary for consideration by the Tax White Paper.

Recommendations

The Inquiry has made 44 recommendations relating to the Australian financial system. The nature of some recommendations warrants more in-depth discussion. These recommendations are shaded darker in the Summary of recommendations by chapter tables on the following pages. The Inquiry considers that the remaining recommendations in the body of the report can be made without providing the reader with the same depth of explanation. Recommendations contained in Appendix 1: Significant matters are only explained briefly.

Summary of recommendations by chapter

| Chapter 1: Resilience (pages 33–88) | |

| Number | Description |

| 1 |

Capital levels

Set capital standards such that Australian authorised deposit-taking institution capital ratios are unquestionably strong. |

| 2 |

Narrow mortgage risk weight differences

Raise the average internal ratings-based (IRB) mortgage risk weight to narrow the difference between average mortgage risk weights for authorised deposit-taking institutions using IRB risk-weight models and those using standardised risk weights. |

| 3 |

Loss absorbing and recapitalisation capacity

Implement a framework for minimum loss absorbing and recapitalisation capacity in line with emerging international practice, sufficient to facilitate the orderly resolution of Australian authorised deposit-taking institutions and minimise taxpayer support. |

| 4 |

Transparent reporting

Develop a reporting template for Australian authorised deposit-taking institution capital ratios that is transparent against the minimum Basel capital framework. |

| 5 |

Crisis management toolkit

Complete the existing processes for strengthening crisis management powers that have been on hold pending the outcome of the Inquiry. |

| 6 |

Financial Claims Scheme

Maintain the ex post funding structure of the Financial Claims Scheme for authorised deposit-taking institutions. |

| 7 |

Leverage ratio

Introduce a leverage ratio that acts as a backstop to authorised deposit-taking institutions' risk-weighted capital positions. |

| 8 |

Direct borrowing by superannuation funds

Remove the exception to the general prohibition on direct borrowing for limited recourse borrowing arrangements by superannuation funds. |

| Chapter 2: Superannuation and retirement incomes (pages 89–142) | |

| Number | Description |

| 9 |

Objectives of the superannuation system

Seek broad political agreement for, and enshrine in legislation, the objectives of the superannuation system and report publicly on how policy proposals are consistent with achieving these objectives over the long term. |

| 10 |

Improving efficiency during accumulation

Introduce a formal competitive process to allocate new default fund members to MySuper products, unless a review by 2020 concludes that the Stronger Super reforms have been effective in significantly improving competition and efficiency in the superannuation system. |

| 11 |

The retirement phase of superannuation

Require superannuation trustees to pre-select a comprehensive income product for members' retirement. The product would commence on the member's instruction, or the member may choose to take their benefits in another way. Impediments to product development should be removed. |

| 12 |

Choice of fund

Provide all employees with the ability to choose the fund into which their Superannuation Guarantee contributions are paid. |

| 13 |

Governance of superannuation funds

Mandate a majority of independent directors on the board of corporate trustees of public offer superannuation funds, including an independent chair; align the director penalty regime with managed investment schemes; and strengthen the conflict of interest requirements. |

| Chapter 3: Innovation (pages 143–192) | |

| Number Description | |

| 14 |

Collaboration to enable innovation

Establish a permanent public–private sector collaborative committee, the 'Innovation Collaboration', to facilitate financial system innovation and enable timely and coordinated policy and regulatory responses. |

| 15 |

Digital identity

Develop a national strategy for a federated-style model of trusted digital identities. |

| 16 |

Clearer graduated payments regulation

Enhance graduation of retail payments regulation by clarifying thresholds for regulation by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission and the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority. Strengthen consumer protection by mandating the ePayments Code. Introduce a separate prudential regime with two tiers for purchased payment facilities. |

| 17 |

Interchange fees and customer surcharging

Improve interchange fee regulation by clarifying thresholds for when they apply, broadening the range of fees and payments they apply to, and lowering interchange fees. Improve surcharging regulation by expanding its application and ensuring customers using lower-cost payment methods cannot be over-surcharged by allowing more prescriptive limits on surcharging. |

| 18 |

Crowdfunding

Graduate fundraising regulation to facilitate crowdfunding for both debt and equity and, over time, other forms of financing. |

| 19 |

Data access and use

Review the costs and benefits of increasing access to and improving the use of data, taking into account community concerns about appropriate privacy protections. |

| 20 |

Comprehensive credit reporting

Support industry efforts to expand credit data sharing under the new voluntary comprehensive credit reporting regime. If, over time, participation is inadequate, Government should consider legislating mandatory participation. |

| Chapter 4: Consumer outcomes (pages 193–232) | |

| Number | Description |

| 21 |

Strengthen product issuer and distributor accountability

Introduce a targeted and principles-based product design and distribution obligation. |

| 22 |

Introduce product intervention power

Introduce a proactive product intervention power that would enhance the regulatory toolkit available where there is risk of significant consumer detriment. |

| 23 |

Facilitate innovative disclosure

Remove regulatory impediments to innovative product disclosure and communication with consumers, and improve the way risk and fees are communicated to consumers. |

| 24 |

Align the interests of financial firms and consumers

Better align the interests of financial firms with those of consumers by raising industry standards, enhancing the power to ban individuals from management and ensuring remuneration structures in life insurance and stockbroking do not affect the quality of financial advice. |

| 25 |

Raise the competency of advisers

Raise the competency of financial advice providers and introduce an enhanced register of advisers. |

| 26 |

Improve guidance and disclosure in general insurance

Improve guidance (including tools and calculators) and disclosure for general insurance, especially in relation to home insurance. |

| Chapter 5: Regulatory system (pages 233–260) | |

| Number Description | |

| 27 |

Regulator accountability

Create a new Financial Regulator Assessment Board to advise Government annually on how financial regulators have implemented their mandates. Provide clearer guidance to regulators in Statements of Expectation and increase the use of performance indicators for regulator performance. |

| 28 |

Execution of mandate

Provide regulators with more stable funding by adopting a three-year funding model based on periodic funding reviews, increase their capacity to pay competitive remuneration, boost flexibility in respect of staffing and funding, and require them to undertake periodic capability reviews. |

| 29 |

Strengthening the Australian Securities and Investments Commission's funding and powers

Introduce an industry funding model for the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) and provide ASIC with stronger regulatory tools. |

| 30 |

Strengthening the focus on competition in the financial system

Review the state of competition in the sector every three years, improve reporting of how regulators balance competition against their core objectives, identify barriers to cross-border provision of financial services and include consideration of competition in the Australian Securities and Investments Commission's mandate. |

| 31 |

Compliance costs and policy processes

Increase the time available for industry to implement complex regulatory change. Conduct post-implementation reviews of major regulatory changes more frequently. |

| Appendix 1: Significant matters (pages 261–276) | |

| Number | Description |

| 32 |

Impact investment

Explore ways to facilitate development of the impact investment market and encourage innovation in funding social service delivery. Provide guidance to superannuation trustees on the appropriateness of impact investment. Support law reform to classify a private ancillary fund as a 'sophisticated' or 'professional' investor, where the founder of the fund meets those definitions. |

| 33 |

Retail corporate bond market

Reduce disclosure requirements for large listed corporates issuing 'simple' bonds and encourage industry to develop standard terms for 'simple' bonds. |

| 34 |

Unfair contract term provisions

Support Government's process to extend unfair contract term protections to small businesses. Encourage industry to develop standards on the use of non-monetary default covenants. |

| 35 |

Finance companies

Clearly differentiate the investment products that finance companies and similar entities offer retail consumers from authorised deposit-taking institution deposits. |

| 36 |

Corporate administration and bankruptcy

Consult on possible amendments to the external administration regime to provide additional flexibility for businesses in financial difficulty. |

| 37 |

Superannuation member engagement

Publish retirement income projections on member statements from defined contribution superannuation schemes using Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) regulatory guidance. Facilitate access to consolidated superannuation information from the Australian Taxation Office to use with ASIC's and superannuation funds' retirement income projection calculators. |

| 38 |

Cyber security

Update the 2009 Cyber Security Strategy to reflect changes in the threat environment, improve cohesion in policy implementation, and progress public–private sector and cross-industry collaboration. Establish a formal framework for cyber security information sharing and response to cyber threats. |

| Appendix 1: Significant matters (pages 261–276) (cont.) | |

| Number | Number |

| 39 |

Technology neutrality

Identify, in consultation with the financial sector, and amend priority areas of regulation to be technology neutral. Embed consideration of the principle of technology neutrality into development processes for future regulation. Ensure regulation allows individuals to select alternative methods to access services to maintain fair treatment for all consumer segments. |

| 40 |

Provision of financial advice and mortgage broking

Rename 'general advice' and require advisers and mortgage brokers to disclose ownership structures. |

| 41 |

Unclaimed monies

Define bank accounts and life insurance policies as unclaimed monies only if they are inactive for seven years. |

| 42 |

Managed investment scheme regulation

Support Government's review of the Corporations and Markets Advisory Committee's recommendations on managed investment schemes, giving priority to matters relating to:

|

| 43 |

Legacy products

Introduce a mechanism to facilitate the rationalisation of legacy products in the life insurance and managed investments sectors. |

| 44 |

Corporations Act 2001

ownership restrictions

Remove market ownership restrictions from the Corporations Act 2001 once the current reforms to cross-border regulation of financial market infrastructure are complete. |

Crisis management toolkit

Recommendation 5

Complete the existing processes for strengthening crisis management powers that have been on hold pending the outcome of the Inquiry.

Description

In September 2012, the previous Government consulted on a comprehensive package, Strengthening APRA's crisis management powers. 63 The CFR has also recommended separate changes to resolution arrangements and powers for FMI. 64 In 2013, these processes were put on hold as part of a Government moratorium on significant new financial sector regulation pending the outcome of this Inquiry. Government should now resume these processes, with a view to ensuring regulators have comprehensive powers to manage crises and minimising negative spill-overs to the financial system, the broader economy and taxpayers.

The Inquiry strongly supports enhancing crisis management toolkits for regulators. It is important for the two processes to be concluded, giving due consideration to industry views on the packages.

Objectives

- •

- Promote a resilient financial system.

- •

- Enable the orderly resolution of distressed financial institutions.

Discussion

Problems the recommendation seeks to address

Given the importance of ADIs, insurers, superannuation funds and FMI to the functioning and stability of the financial system and economy, regulators need comprehensive powers to facilitate the orderly resolution of these institutions.

Responding to local and global changes, CFR agencies reviewed the existing legislative provisions for prudentially regulated institutions and FMI. These reviews paid close attention to international standards and developments, particularly G20 and FSB initiatives to promote resilient financial systems and frameworks that resolve financial distress, including the FSB Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions (Key Attributes). 65 Although Australia has strong frameworks, the reviews identified gaps and areas that could be strengthened.

The Government consultation paper Strengthening APRA's crisis management powers canvassed a number of options in relation to all APRA-regulated industries. The package does not include statutory bail-in powers outlined in the Key Attributes or general structural requirements, such as ring-fencing, being pursued in some jurisdictions. It includes:

- •

- Directions powers, including clarifying that APRA may direct a regulated institution to pre-position for resolution — that is, require changes at an institution to make it more feasible to successfully resolve that institution if it were to fail.

- •

- Group resolution powers, including extending certain powers to authorised non-operating holding companies (NOHCs) and subsidiaries in a range of distress situations.

- •

- Powers to assist with resolving branches of foreign banks.

The CFR recommendations for strengthening the crisis management framework for FMI included:

- •

- Introducing a specialised resolution regime for FMI.

- •

- Clarifying the application of location requirements for FMI operating across borders.

Since these processes were put on hold, international developments have included updates to the Key Attributes, yielding additional guidance on areas such as

cross-border information sharing, and resolving FMI and FMI participants. Some countries have also introduced structural reforms, such as mandating a form of ring-fencing, or a NOHC structure for institutions with certain risk profiles or of a certain size, with the aim of improving resolvability. These approaches emphasise reducing risks to core banking activities from more complicated and risky forms of banking, and simplifying institutions to make them more easily resolved.

Conclusion

The Inquiry believes progressing the packages would deliver a substantial net benefit. A range of resolution options — more 'tools in the toolkit' — would maximise the likelihood that a viable option will be available in any given situation to achieve an orderly resolution. The Inquiry notes the high costs associated with the disorderly failure of an institution, particularly where this creates financial system instability or the need for Government support. The Inquiry also notes that many of the proposed powers would have a limited regulatory burden in normal times.

In relation to the package of resolution powers for APRA, industry submissions largely support the package, although they raise practical and legal issues with some of the proposals. 66

APRA's submission to the Inquiry stresses the vital role that crisis management powers play in the prudential framework. 67 In any future crisis, these reforms would provide a wider range of tools, making it more likely that a credible, low-cost option for preventing a disorderly failure could be found, without risking taxpayer funds.

The RBA advocates for progressing the CFR proposals on FMI regulation as a matter of priority. 68 It notes that the continuity of FMI services is critical for the financial system to function. In addition, the RBA notes that, where FMI is domiciled offshore, Australian regulators need to have sufficient influence to prevent Australian functions from being compromised in a resolution.

The Inquiry does not recommend pursuing industry-wide structural reforms such as ring-fencing. These measures can have high costs, and require changes for all institutions regardless of the institution-specific risks. Neither APRA nor the RBA nor the banking industry saw a strong case for these reforms.

Nevertheless, APRA submits that it may be beneficial to require structural changes for specific institutions in some situations, where substantial risks or significant organisational complexity may impede supervision or an orderly resolution. The powers included in the consultation package provide sufficient flexibility to do this effectively.

Given the time that has passed since the initial consultation in progressing the reform packages — in particular, the considerable international developments over this period — a view should be taken as to whether additional proposals warrant inclusion.

All proposals should go through the appropriate consultation, regulatory assessment and compliance cost assessment processes.

63 Treasury 2012, Strengthening APRA's Crisis Management Powers: Consultation Paper, Commonwealth of Australia, Canberra.

64 Stevens, G 2012, 'Review of Financial Market Infrastructure Regulation', letter to The Hon. Wayne Swan, MP, Deputy Prime Minister and Treasurer, 10 February

65 Financial Stability Board (FSB) 2014, Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes for Financial Institutions, FSB, Basel.

66 Submissions on the consultation paper are available on the Treasury website, viewed 11 November 2014,

http://www.treasury.gov.au/ConsultationsandReviews/Consultations/2012/APRA/ Submissions .

67 Australian Prudential Regulation Authority 2014, Second round submission to the Financial System Inquiry, page 38.

68 Reserve Bank of Australia 2014, First round submission to the Financial System Inquiry, page 4.

IMF Financial Sector Assessment Program, 2019 Financial System Stability Assessment (Australia)

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The Australian authorities have taken welcome steps to further strengthen the financial system since the previous FSAP. Bank capital requirements have been raised and applied more conservatively than minimum Basel standards. Funding risks have been lowered. Financial supervision and systemic risk oversight have been enhanced. And the authorities have taken successful policy action to calm rapid growth in riskier segments of the mortgage market.

The system nonetheless faces challenges. Stretched real estate valuations and high household leverage pose significant macrofinancial risks. 27 years of uninterrupted growth, low inflation, low policy rates, tax incentives, and easy credit have stimulated a rise in household debt and fueled a build-up of real estate exposure in a concentrated banking system, which together with pension ('superannuation") funds dominates the large Australian financial sector. Household debt has risen by some 25 percentage points since the previous FSAP to about 190 percent of disposable income, one of the highest levels in the world. Banks continue to draw extensively on overseas wholesale funding, though reliance has declined in recent years. The ongoing Royal Commission (RC) inquiry has revealed a pattern of misconduct in the financial sector, including at the four major banks that comprise 80 percent of the system.

The major banks run similar business models, raising the vulnerability of the system to a common shock. All are heavily exposed to real estate—residential forming about 60 percent of loans, and commercial (CRE) a further 7 percentage points. Wholesale funding dependence has diminished but remains around one-third of total funding, of which nearly two-thirds is from international sources. Banks' direct international exposures are mainly to New Zealand, where subsidiaries of the four major Australian banks play a dominant role in the banking system.

Bank solvency appears relatively resilient to stress. A test of resilience to a combination of a significant slowdown in China, a severe correction in real estate valuations, and a marked tightening of global financial conditions, revealed some pressures on capital, although the 10 largest banks would all still meet regulatory minima. Liquidity pressures may arise more abruptly. Given high maturity transformation, banks' continued reliance on overseas wholesale funding leaves them exposed to global liquidity shocks.

Policy action has lowered financial stability risks. Restrictions on the growth of investor loans and the share of interest-only mortgages, as well as the introduction of stronger lending standards, appear to have led to a slowdown in mortgage credit growth, and the housing market is now cooling. Given this background, additional tightening measures do not appear warranted at this juncture, though, given prevailing vulnerabilities, the authorities should stand ready to recalibrate policies as necessary to continue to reduce systemic risk. Over time, broader tax reforms could reduce structural incentives for leveraged investment by households, including in residential real estate. Further reduction in banks' use of wholesale funding and extension of the duration of their liabilities would help to lower structural funding risks.

Australia benefits from a robust regulatory framework. Financial supervision shows generally high conformity to international best practices, although there are opportunities to close identified gaps and strengthen arrangements. Steps are recommended to bolster the independence and resourcing of the regulatory agencies, by removing constraints on their policy making powers and providing additional budgetary autonomy and flexibility.

Enforcement powers should be strengthened, and their use expanded, to support effective risk management and mitigate future misconduct. Supervisory approaches would also be enhanced by periodic in-depth reviews of banks' governance and risk management, and by improving coordination of supervision of internationally active insurance groups.

Greater formalization and transparency of the work of the Council of Financial Regulators (CFR) would further buttress the financial stability framework. While the authorities have a strong track record of addressing financial stability issues in a productive and collaborative manner, the current arrangements are informal, and there is limited transparency surrounding the work of the Council. Greater formalization could further strengthen collaboration, boost confidence in the collective work of the regulatory agencies, and guard against possible delay in addressing nascent systemic risks. The CFR is encouraged to boost transparency by publishing records of its meetings and tabling an Annual report to Parliament, highlighting the identification of systemic risks and actions taken to mitigate them.

Additional investment in data and analytical tools would strengthen financial supervision and systemic risk oversight. Relative to international experience, the assessment identified shortfalls in the granularity and consistency of data to support the analysis of supervisory and systemic risks and the formulation of policy. The CFR agencies are recommended to conduct a major review of potential data needs and implement improvements, publishing the resulting data where feasible.

Improved data would also facilitate enhancements in stress testing and support closer integration of the results into prudential supervision, crisis preparedness and policy discussions. It would also help harness the collective expertise of the Reserve Bank (RBA) and the Australia Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA) in the analysis and evaluation of policy options.

Expansion of the set of policy tools would enhance flexibility to address systemic risk and structural vulnerabilities. A 'readiness' assessment of potential policy options would enable the authorities to address the associated data requirements and tackle any legal or regulatory obstacles to their use. Priorities for review include DTI/DSTI and LTV restrictions, time-varying risk weights, as well as tools to address risks from nonbanks and from highly cyclical assets such as CRE.

Reinforcing financial crisis management arrangements is a priority. Encouraging progress has been made in strengthening APRA's resolution powers and expanding banks' recovery planning to cover additional institutions. Building on this progress, there is scope for better integration of banks' recovery planning into their risk management framework. It is also important to complete the resolution policy framework quickly, to ensure that banks expand their loss absorbency capacity to bear the costs of their own failure. Bank-specific resolution plans should be rolled out and validated swiftly. The Australian and New Zealand authorities have developed a strong and effective supervisory relationship, but there is a need to advance mutual understanding of approaches to resolution in order to establish clear cross-border bank resolution modalities. Some progress has also been made in developing a resolution framework for Financial Market Infrastructures (FMIs) and its finalization is a priority.

| Table 1. Australia: FSAP Key Recommendations | |

| Recommendations and Authority Responsible for Implementation | Time 1 |

| Banking and Insurance Supervision | |

| Strengthen the independence of APRA and ASIC, by removing constraints on policy making powers and providing greater budgetary and funding autonomy; strengthen ASICs enforcement

powers and expand their use to mitigate misconduct (Treasury, APRA, ASIC). |

ST |

| Enhance APRA's supervisory approach by carrying out periodic in-depth reviews of governance and risk management (APRA). | ST |

| Strengthen the integration of systemic risk analysis and stress testing into supervisory processes (APRA, RBA). | I |

| Financial Stability Analysis | |

| Commission and implement results of a comprehensive forward-looking review of potential data needs. Improve the quantity, quality, granularity and consistency of data available to the CFR agencies to support financial supervision, systemic risk oversight and policy formulation (CFR

agencies). |

MT |

| Enhance the authorities' monitoring, modeling and stress testing framework for assessing solvency, liquidity and contagion risk. Draw on the results to inform policy formulation and evaluation (CFR agencies). |

ST |

| Encourage further maturity extension and lower use of overseas wholesale funding (APRA). | I |

| Systemic Risk Oversight and Macroprudential Policy | |

| Raise formalization and transparency of the CFR and accountability of its member agencies through publishing meeting records as well as publication and presentation of an Annual Report to Parliament by CFR agency Heads (CFR agencies). |

I |

| Undertake a CFR review of the readiness to apply an expanded set of policies to address systemic risks, including data and legal/regulatory requirements; and address impediments to their deployment (CFR agencies). |

I |

| Commission analysis by the CFR member agencies on relevant financial stability policy issues, including: policies affecting household leverage; as well as factors affecting international investment flows and their implications for real estate markets (CFR agencies). |

MT |

| Financial Crisis Management and Safety Nets | |

| Complete the resolution policy framework and expedite development of resolution plans for large and mid-sized banks and financial conglomerates, and subject them to annual supervisory review (APRA, Treasury). | ST |

| Extend resolution funding options by expanding loss-absorption capacity for large and mid-sized banks and introduce statutory powers (APRA, Treasury). | ST |

| Advance mutual understanding between the Australia and New Zealand resolution authorities on cross-border bank resolution modalities, through the Trans-Tasman Banking Council

(CFR agencies). |

ST |

| Financial Market Infrastructures | |

| Strengthen independence of RBA and ASIC for supervisory oversight, enhance enforcement powers and promote compliance with regulatory requirements (RBA, ASIC, Treasury). | I |

| Finalize the resolution regime for FMIs in line with the FSB Key Attributes (RBA, ASIC, Treasury). | ST |

| Anti-Money Laundering / Countering the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) | |

| Expand the AML/CFT regime to cover all designated non-financial businesses and professions (DNFBPs) and strengthen AML/CFT supervision by: improving data collection and risk analysis; increasing oversight of controls and compliance; and undertaking more formal enforcement action in the event of breaches (Department of Home Affairs, Treasury, AUSTRAC).

1 I Immediate (within 1 year); ST Short -term (within 1–2 years); MT Medium-term (within 3–5 years) |

I |

40. While AUSTRAC has the authority to oversee banks' AML/CFT systems, its significant reliance on banks' self-reporting of weaknesses has not always proved effective. Recent events have shown that some banks' processes for ensuring compliance with AML/CFT requirements have not worked as reported, which have resulted in failure to comply with rules and laws. AUSTRAC should enhance its supervisory approach by performing end-to-end periodic thematic reviews of AML/CFT systems particularly for major banks and should take swift formal action to address weaknesses and critical compliance issues.

E. Financial Market Infrastructures 32

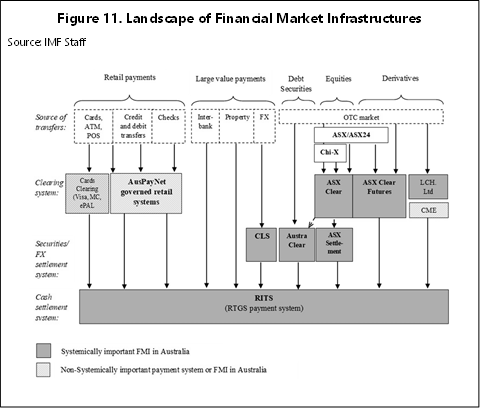

41. Financial Market Infrastructures (FMIs) in Australia generally operate reliably, and the competitive landscape has seen new entrants and competitors emerge. The Reserve Bank Information and Transfer System (RITS), operated by the RBA, is the only domestic systemically important interbank payment system. In addition, the domestically incorporated Australian Securities Exchange (ASX) group operates an integrated infrastructure including trading platforms, two central counterparties (CCPs) and two securities settlement systems (SSSs) (Figure 11). Since 2011, the ASX has faced competition from foreign infrastructures in some markets, including Chi-X for cash equities trading and the London Clearing House Limited (LCH Ltd) and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) for some over the counter (OTC) derivatives clearing.

42. FMIs are subject to strong supervisory oversight though enforcement powers should be strengthened further. Supervisory oversight of FMIs by the RBA and ASIC is well-established, with supervisory expectations importantly strengthened over the past few years. Legal and regulatory frameworks for FMIs are generally clear and transparent; and regulatory requirements sufficiently detailed due to the adoption of the PFMI and subsequent guidance. The FSAP recommends that the authorities strengthen enforcement powers for the supervision of CCPs and SSSs to promote compliance with regulatory requirements and to take corrective actions in accordance with the PFMI, as well as to promote effective competition between FMIs (given that one entity operates several systemic FMIs). Steps should also be taken to further enhance already close cooperation between domestic and foreign authorities in case of a crisis event affecting FMIs.

43. Further attention is warranted to strengthen ASX Clear's governance and risk management framework to promote compliance with the authorities' guidelines. ASX Ltd and the authorities are encouraged to consider the impact of the current governance structure on compliance with risk management requirements. Additional improvements to risk management systems should be considered to facilitate separation of house and client accounts, implementation of concentration limits on collateral, holding of adequate pre-funded liquid resources and improvements in the operation of intraday margin calls. Operational risks should also be further addressed.

44. The authorities should prioritize finalization of the special resolution regime for FMIs. Some progress has already been made. The CFR authorities are in the process of drafting legislation that establishes a resolution regime for FMIs consistent with international standards and that incorporates feedback from stakeholders on a past consultation paper. 33 To finalize the regime, the authorities will need to address issues specific to Australia's financial market structure, such as clearing and settlement facilities that are part of a vertically-integrated exchange group, the dominance of a few domestic financial institutions and a few global banks, and issues regarding the diversity and capacity of private liquidity providers.

33 See "Resolution Regime for Financial Market Infrastructures," Treasury, February 2015, and "Resolution Regime for Financial Market Infrastructures: Response to Consultation," CFR, November 2015.

34 Australia was assessed jointly by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and the Asia-Pacific Group on Money Laundering. The mutual evaluation report (MER) was adopted on February 27, 2015 and published on April 21, 2015, see

http://www.fatf-gafi.org/countries/a-c/australia/documents/mer-australia-2015.html .

35 FATF has upgraded Australia's ratings on seven Recommendations, see

http://www.fatf- gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/fur/FUR-Australia-2018.pdf . Australia remains in the FATF's enhanced follow-up process because 14 Recommendations remain non- or partially- compliant, including several related to priority improvements identified in the MER.

36 Financial intelligence is analysis derived from reports submitted to FIUs and from other information sources, aimed at assisting criminal investigations into money laundering, its underlying offences or terrorist financing by: identifying the extent of criminal networks and/or the scale of criminality; identifying and tracing the proceeds of crime, terrorist funds or any other assets that are, or may become, subject to confiscation; and developing evidence, which could be used in criminal proceedings.

IMF Financial Sector Assessment Program, 2019 Technical Note – Supervision, Oversight and Resolution Planning on Financial Market Infrastructures

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Financial Market Infrastructures (FMIs) in Australia generally operate reliably, and the competitive landscape has seen new entrants and competitors emerge. The Reserve Bank Information and Transfer System (RITS), operated by the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), is the only domestic systemically important interbank payment system. In addition, the domestically incorporated ASX Limited (ASX) group operates an integrated infrastructure including trading platforms, two central counterparties (CCPs), and two securities settlement systems (SSSs). Since 2011, the ASX has faced competition from foreign infrastructures in some markets, including Chi-X Australia Pty Ltd (Chi-X) for cash equities trading and the LCH Limited (LCH Ltd) and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) for some over the counter (OTC) derivatives clearing.

Supervision and oversight of FMIs is well-established with supervisory expectations importantly strengthened over the past few years. The Australian authorities responsible for the regulation, supervision, and oversight of FMIs are the RBA and the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC). The RBA has sole responsibility for payment systems, while ASIC and the RBA have complementary regulatory responsibilities for CCPs and SSSs. The FSAP assessment is that Clearing and Settlement (CS) facility 2 supervision and oversight are strong and that the FMI legal and regulatory framework generally is clear and transparent. The adoption of the CPSS-IOSCO Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures (PFMI) and subsequent guidance has strengthened the authorities' approach with more comprehensive requirements and assessments, as well as increased diligence in following up on findings. Cooperation among the authorities is close, both domestically as well as with foreign authorities, although cooperation frameworks need to be further developed to manage FMI crisis events. The mission recommends the RBA consider updating its approach to payment systems oversight, in particular to increase the transparency around expectations for potential (privately operated) systemically important payment systems.

Enforcement powers for the supervision of CCPs and SSSs should, however, be strengthened in accordance with the PFMI. Currently, the RBA has no independent enforcement powers to underpin its oversight. The RBA may request that ASIC issue a direction to comply with the FSS or to reduce systemic risk; however, ASIC is not required to do so. Furthermore, the Minister may overrule ASIC's decision regarding whether to make or to revoke a direction. Although there is no evidence of such intervention by the Minister (and, in fact the Minister has delegated certain responsibilities to ASIC), the current legal basis for enforcing corrective actions should be strengthened with independent powers for the RBA. It also is recommended that legislation should grant ASIC and the ACCC the powers to promote fair and effective competition between FMIs, as such powers are lacking. Supervisory powers could be broadened, for example, by granting rule writing powers in addition to directions powers.

The Australian authorities have made some progress in formulating a special resolution regime for FMIs. In 2015, the Australian government issued a high-level consultation paper to establish a special resolution regime for CS facilities (and trade repositories) consistent with international standards. It requested feedback on the scope of the resolution authority, resolution and directions powers, safeguards and funding arrangements, and international cooperation. The CFR authorities are developing drafting instructions for legislation that would establish a resolution regime for FMIs.

2 CCPs and SSSs jointly are called Clearing and Settlement (CS) facilities under the Australian Corporations Act 2001.

The government should prioritize finalization of its special resolution regime for domestic FMIs, since it currently lacks the necessary framework and tools to resolve an FMI. The authorities will need to address issues specific to Australia's financial market structure, such as CS facilities that are part of a vertically-integrated exchange group, the dominance of a few domestic financial institutions and a few global banks in the Australian financial market, and issues regarding the diversity and capacity of private-sector liquidity providers. This specific structure will have an important bearing on the decisions that the Australian government will have to make regarding the breadth of the authorities' powers. Important considerations include the treatment of affiliated entities within groups, including the implications for the point-of-entry strategy, and the breadth of ex-ante resolvability assessments and FMI resolution plans.

New supervisory challenges, in particular related to cyber risks and new technologies, are appropriately addressed by ASIC and the RBA; nevertheless, cyber resilience of FMIs would further benefit from industry-wide cyber tests. RITS and ASX's CS facilities are subject to regular cyber resilience assessments by the authorities against CPMI-IOSCO guidance, international standards, and good practices. Authorities could supplement these with industry-wide cyber resilience tests to gain insights into the impact of a cyber incident on the industry as a whole. With regard to distributed ledger technology (DLT) and other new technologies, ASIC's and RBA's approach includes monitoring developments and specifying expectations. Supervision of the replacement of ASX's CS systems, which uses DLT technology, can be fully addressed within the existing regulatory framework. It involves a permissioned model, where only ASX, clearing members, and issuers would be authorized to participate. Private contractual information would be available only to the transaction parties, and ASX would be the only permissioned writer to the ledger.

The FSAP's assessment of elements of ASX Clear's governance and risk management framework identified several areas where further attention is warranted. ASX Ltd and the authorities are encouraged to consider the impact of the current governance structure on compliance with CS risk management requirements, including whether a simpler structure would help meet requirements related to competition issues in the equity market more easily. The planned FMI resolution regime will also have to address the integrated functions and any resulting obstacles to the FMI's resolvability. ASX Clear's recovery plan should address its reliance on parent funding and on other group services. Further improvements to its risk management systems should be considered, such as the operational capacity to implement intraday margin calls, separate house and client accounts, implementation of concentration limits on collateral, and availability of sufficient pre-funded liquid resources before applying mechanical liquidity allocation mechanisms. Operational risks need to be further addressed in line with authorities' requirements.

| Table 1. Australia: Recommendations for FMI Supervision, Oversight, and Resolution | ||

| Recommendations for the Supervision and Oversight of FMIs | Timing 1 | Responsibility |

| Increase transparency of regulatory expectations for potential (privately operated) systemically important payment systems. | ST | RBA |

| Strengthen legal basis of direction powers for supervision of CS facilities, with independence from the Minister and own powers for the RBA. | I | ASIC, RBA,

Treasury |

| Broaden the suite of enforcement tools for CS facilities. | ST | ASIC, RBA,

Treasury |

| Strengthen the legal and regulatory frameworks in the area of fair and effective competition among CS facilities. | I | ASIC, RBA,

Treasury, ACCC |

| Complement cyber resilience assessments with industry-wide tests. | ST | CFR |

| Enhance the crisis communication framework for authorities for/supervisors of CS facilities. | ST | ASIC, RBA |

| Update MOUs with ACCC on CS facilities matters. | ST | RBA, ASIC, ACCC |

| Streamline cooperation agreements with New Zealand authorities for ASX Clear (Futures). | ST | RBA, ASIC, RBNZ, FMA |

| Recommendations for the FMI Resolution Framework | ||

| Finalize the proposed special resolution regime for FMIs. | I | CFR |

| Address challenges related to current and potential FMI structure(s), and FMI- specific, FMI group, FMI linkages, and inter-dependency factors. | I | CFR |

| Include broad directions powers in the Australian resolution regime to conduct resolvability assessments and improve FMI resolvability ex ante. Ensure a streamlined and timely process for issuance of directions. |

I |

CFR |

| Include broad powers in the Australian resolution regime to appoint a statutory manager to resolve a distressed, failing, or failed FMI. | I | CFR |

| Include broad powers in the Australian resolution regime to transfer critical FMI functions to a solvent third party or bridge FMI. | I | CFR |

| Ensure appropriate staffing with necessary knowledge and expertise regarding resolution of systemically-important FMIs. | I | RBA, ASIC, and

Treasury |

| Recommendations to strengthen ASX Clear's observance of the PFMI | ||

| Clarify the point at which settlement is final in the operating rules. | I | ASX Clear and ASX Settlement |

| Address procyclicality through the annual validation process for margin models. | ST | ASX Clear |

| Consider ring-fencing CS facilities within the ASX group structure through a dedicated ERM, risk committee, staff, and risk management systems. | ST | ASX |

| Address group interdependencies fully in ASX Clear's recovery plan. | I | ASX Clear |

| Replace the aging CHESS system with modern technology to increase operational reliability and support compliance with financial risk management requirements (e.g., operational capacity to conduct intraday margin calls and segregated house and client accounts). |

ST-MT |

ASX Clear |

| Increase and diversify qualifying liquid resources to move the use of OTAs to a later stage in the waterfall. | I | ASX Clear |

| Apply concentration limits on collateral and broaden the range of eligible collateral to include government and semi-government bonds. | I | ASX Clear |

| 1 I–Immediate (within 1 year); ST–Short-term (within 1 to 2 years); MT–Medium-Term (within 3 to 5 years). | ||

Overseas Clearing and Settlement Facilities: The Australian Licensing Regime, 2015 Consultation Paper, Council of Financial Regulators

Introduction

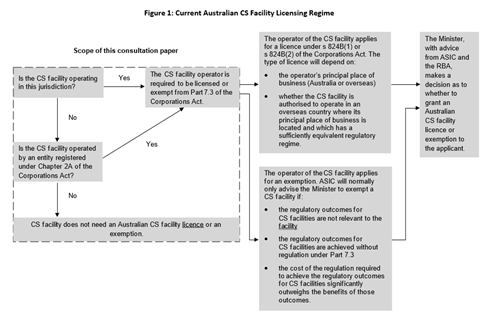

The increasingly global nature of many financial markets, combined with regulatory reforms, has prompted increased participation by domestic financial institutions in overseas clearing and settlement (CS) facilities. A number of overseas CS facilities have also recently begun, or expressed interest in, providing CS services that may be relevant to the safe, efficient and effective functioning of the Australian financial system, or confident, fair and effective dealings in financial products by Australian CS facility users.

Alongside these developments, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) and the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) are receiving an increasing number of queries regarding whether certain overseas CS facilities fall within the scope of the licensing regime under Part 7.3 of the Corporations Act 2001 (Corporations Act). These queries have arisen primarily due to a lack of clarity around whether, for the purposes of the Corporations Act, an overseas CS facility is 'operating in this jurisdiction'. This is the threshold that determines whether a CS facility must be either licensed or exempted from Part 7.3 of the Corporations Act.

The Council of Financial Regulators (CFR) considers that there is a case to provide greater clarity, to the extent practicable, regarding the circumstances in which a CS facility must be either licensed in Australia or exempted from Part 7.3 of the Corporations Act. While ASIC has issued guidance that sets out a number of non-exhaustive factors that it would consider in assessing whether a CS facility is operating in this jurisdiction, 1 greater clarity in legislation and accompanying regulation would provide increased legal certainty for overseas CS facilities and their participants.

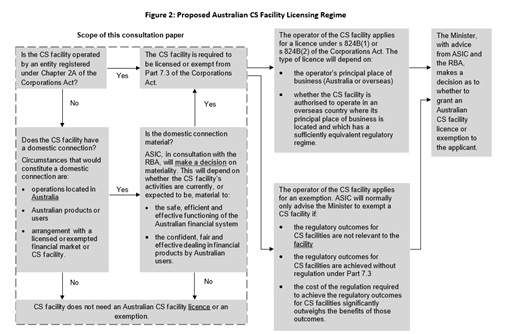

This consultation seeks preliminary views on legislative change as part of the CFR's ongoing consideration of the cross-border regulation of CS facilities. Any legislative change will ultimately be a matter for the government to consider.

This paper proposes a new approach to assessing whether an 'overseas' CS facility (i.e. a CS facility that is not operated by a body corporate registered under Chapter 2A of the Corporations Act) must be either licensed in Australia or exempted from Part 7.3 of the Corporations Act. The proposal rests on a test of the materiality of the CS facility's connection to the Australian financial system. ASIC, in consultation with the RBA, will make a determination about whether a CS facility's activities are material for the purposes of this test. The purpose of this proposal is to promote Australian entities' access to a diverse range of CS options, both in Australia and overseas, by providing clarity to all stakeholders on the scope of the Australian CS facility licensing regime.

It is not expected that the proposed new approach would result in additional CS facilities being within the scope of Australia's CS facility licensing regime, and the rest of the Australian CS facility licensing regime would remain unchanged. The factors relevant to a consideration of the materiality of a CS facility's connection to the Australian financial system by ASIC and the RBA (together, the regulators) are already listed in ASIC's Regulatory Guide 211 – Clearing and Settlement Facilities: Australian and Overseas Operators (RG 211). Rather, the proposed new approach formalises how these factors are currently, and in the future will be, weighed in reaching judgements around regulatory scope so as to provide clarity and transparency for prospective future CS facility licence applicants.