Explanatory Memorandum

(Circulated by authority of the Assistant Minister for Competition, Charities and Treasury, the Hon Dr Andrew Leigh MP)Glossary

This Explanatory Memorandum uses the following abbreviations and acronyms.

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| AASB | Australian Accounting Standards Board |

| Activities Test | Activities Test as defined in the GloBE Rules |

| ADJR Act 1977 | Administrative Decisions (Judicial Review) Act 1977 |

| Acceptable FAS | Acceptable Financial Accounting Standard |

| Agreed Administrative Guidance | The following collection of documents:

|

| Assessment Bill | Taxation (Multinational—Global and Domestic Minimum Tax) Bill 2024 |

| ATO | Australian Taxation Office |

| Authorised FAS | Authorised Financial Accounting Standard |

| CFS | Consolidated Financial Statements |

| Commentary | Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy – Commentary to the Global Anti-Base Erosion Model Rules (Pillar Two) published by the OECD on 14 March 2022 and amended from time to time |

| Commissioner | Commissioner of Taxation |

| Consequential Bill | Treasury Laws Amendment (Multinational—Global and Domestic Minimum Tax) (Consequential) Bill 2024 |

| DMT | Domestic Minimum Tax |

| ETR | Effective Tax Rate |

| FANIL | Financial Accounting Net Income or Loss |

| FITO | Foreign Income Tax Offset |

| GloBE Rules | OECD GloBE Model Rules (as modified by the Commentary, Agreed Administrative Guidance and Safe Harbour Rules) |

| IIR | Income Inclusion Rule as defined in the GloBE Rules |

| Imposition Bill | Taxation (Multinational—Global and Domestic Minimum Tax) Imposition Bill 2024 |

| ITAA 1936 | Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 |

| ITAA 1997 | Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 |

| JV | Joint Venture |

| LTCE | Low-Taxed Constituent Entity |

| Minimum Tax law | Imposition Bill, Assessment Bill and Consequential Bill |

| MOCE | Minority-owned Constituent Entity |

| MNE | Multinational Enterprise |

| MNE Group | MNE Group as defined in the GloBE Rules |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development |

| OECD GloBE Model Rules | Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy – Global Anti-Base Erosion Model Rules (Pillar Two) published by the OECD on 20 December 2021 |

| OECD Model Tax Convention | OECD (2017), Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital: Condensed Version 2017 |

| QIIR | Qualified Income Inclusion Rule |

| RBA | Reserve Bank of Australia |

| Rules | The Rules empowered to be made under the Assessment Bill or Consequential Bill. |

| Safe Harbour Rules | Safe Harbours and Penalty Relief: Global Anti-Base Erosion Rules (Pillar Two) published by the OECD on 20 December 2022 as well as Agreed Administrative Guidance published by the OECD on 17 July 2023 and 18 December 2023 |

| TAA | Taxation Administration Act 1953 |

| UPE | Ultimate Parent Entity as defined in the GloBE Rules |

| UTPR | Undertaxed Profits Rules as defined in the GloBE Rules |

Overview and context for the Two-Pillar Solution in Australia

On 8 October 2021, Australia and 135 other members of the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (the Inclusive Framework) agreed to the 'Statement on the Two-Pillar Solution to Address the Tax Challenges Arising from the Digitalisation of the Economy' (the Two-Pillar Solution). The Two-Pillar Solution seeks to reform the international taxation rules and ensure that MNEs pay a fair share of tax wherever they operate and generate profits in today's digitalised and globalised world economy. The Two-Pillar Solution is a result of an OECD and G20 policy process with involvement of 140 countries and jurisdictions.

The Two-Pillar Solution is intended to be achieved through a series of tax reforms, including through the ratification of multilateral conventions and instruments. Different reforms are scheduled on different timeframes but are generally to be implemented as a coordinated approach across jurisdictions, with the earliest reforms taking effect from 1 January 2024.

The Two-Pillar Solution is comprised of Pillar 1 and Pillar 2. Pillar 1 aims to ensure a fairer distribution of profits and taxing rights among countries with respect to certain large MNEs. The GloBE Rules under Pillar 2 ensure that in-scope MNEs will be subject to a global minimum tax rate of 15 per cent. This is achieved through a set of rules which identify low taxed pools of income within a MNE Group and which allow parent jurisdictions, or in some cases, other jurisdictions, to claim taxing rights over that income.

The Australian Government announced its intention to implement key aspects of Pillar 2 in the 2023-24 Budget, as part of its continuing efforts to ensure MNEs pay their fair share of tax.

The charging provisions in the GloBE Rules are composed of the IIR and the UTPR.

The Assessment Bill also implements a domestic minimum top-up tax in respect of Constituent Entities located in Australia that are subject to an ETR below the 15 per cent minimum rate.

The IIR applies by allocating the top-up tax to the Parent Entity generally closest to the top of the corporate structure (the 'top-down' approach). The top-up tax relates to LTCEs that are subject to an ETR below the 15 per cent minimum rate in that jurisdiction.

The UTPR serves as a backstop to the IIR. It permits other jurisdictions to impose top-up tax (by denying deductions or an equivalent adjustment) on certain Constituent Entities to the extent that an LTCE in the MNE Group is not subject to tax under an IIR.

The two sets of rules provide a systematic solution to ensure all in-scope MNE Groups are subject to a minimum of 15 per cent ETR in the jurisdictions in which they operate.

These three Bills form part of a set of legislation required to implement a global and domestic minimum tax in Australia:

- •

- Imposition Bill: Taxation (Multinational—Global and Domestic Minimum Tax) Imposition Bill 2024;

- •

- Assessment Bill: Taxation (Multinational—Global and Domestic Minimum Tax) Bill 2024; and

- •

- Consequential Bill: Treasury Laws Amendment (Multinational—Global and Domestic Minimum Tax) (Consequential) Bill 2024.

The Imposition Bill imposes top-up tax, namely Australian DMT tax, Australian IIR tax and Australian UTPR tax.

The Assessment Bill implements the framework for imposition of top-up tax for the IIR, UTPR and the DMT consistent with the GloBE Rules.

The Consequential Bill contains consequential and miscellaneous provisions necessary for the administration of top-up tax, consistent with the existing administrative framework under Australian tax law and the GloBE Rules.

Australian DMT tax and Australian IIR tax apply for Fiscal Years beginning on or after 1 January 2024. Australian UTPR tax applies for Fiscal Years beginning on or after 1 January 2025.

General outline and financial impact

Chapter 1: Taxation (Multinational—Global and Domestic Minimum Tax) Bills

Outline

Chapter 2 The Bills implement a 15 per cent global minimum tax and Australian domestic minimum tax on certain MNEs with annual global revenue of at least EUR 750 million.

Date of effect

The Assessment Bill commences the day after Royal Assent.

For Australian IIR tax and Australian DMT tax, the Assessment Act applies in relation to Fiscal Years starting on or after 1 January 2024. For Australian UTPR tax, the Assessment Act applies in relation to Fiscal Years starting on or after 1 January 2025.

The Consequential and Imposition Bills commence at the same time as the Assessment Bill. However, the provisions of those Bills do not commence at all if the Assessment Bill does not commence. Similarly, these provisions apply in relation to Fiscal Years commencing on or after 1 January 2024, with the exception of the amendment to the International Tax Agreement Act 1953 applying on a prospective basis only. This amendment provides a legislative instrument making power to determine that a certain provision of one of Australia's bilateral double tax agreements (such as the Exchange of Information Article) takes priority over other tax laws.

Proposal announced

The Bills fully implement the 'Implementation of a global minimum tax and a domestic minimum tax' measure in the 2023-24 Budget.

Financial impact

The Bills have the following estimated revenue implications:

All figures in this table represent amounts in $m.

| 2022-23 | 2023-24 | 2024-25 | 2025-26 | 2026-27 |

| - | - | - | 160.0 | 210.0 |

Impact Analysis

The Office of Impact Analysis (OIA) has been consulted an impact analysis (IA) is required, OIA reference Number: 22-01540

Human rights implications

The Assessment Bill, the Consequential Bill and the Imposition Bill do not engage human rights issues. See Statement of Compatibility with Human Rights — Chapter 4.

Compliance cost impact

The Bills are expected to increase compliance costs for in-scope MNEs.

Chapter 1: Taxation (Multinational - Global and Domestic Minimum Tax) Imposition Bill 2024

Outline of chapter

1.1 This Chapter explains the operation of the Taxation (Multinational—Global and Domestic Minimum Tax) Imposition Bill 2024 (Imposition Bill).

Summary of new law

1.2 The Imposition Bill is a taxation bill which imposes global and domestic minimum taxes in respect of profits of MNEs that have been undertaxed. In these explanatory materials, these taxes are referred to as top-up taxes.

Detailed explanation of new law

1.3 To comply with section 55 of the Constitution the Imposition bill deals only with the imposition of top-up tax.

1.4 The top-up tax is as follows:

- •

- Tax payable in accordance with subsection 8(1) of the Assessment Bill (Australian DMT tax) is imposed.

- •

- Tax payable in accordance with subsection 6(1) of the Assessment Bill (Australian IIR tax) is imposed.

- •

- Tax payable in accordance with subsection 10(1) of the Assessment Bill (Australian UTPR tax) is imposed. [Section 3 of the Imposition Bill]

Commencement, application, and transitional provisions

1.5 The Imposition Bill commences at the same time as the Assessment Bill. [Table item 1 in subsection 2(1) of the Imposition Bill]

1.6 However, if the Assessment Bill does not receive Royal Assent, then the Imposition Bill does not commence and top-up tax cannot apply. This ensures that all related legislation must be enacted before top-up tax can apply. The effect of this is that, if Royal Assent is obtained, Australian DMT tax and Australian IIR tax imposed under subsections 8(1) and 6(1) of the Assessment Bill respectively, apply for Fiscal Years commencing on or after 1 January 2024 and Australian UTPR tax, imposed under subsection 10(1) of the Assessment Bill, applies for Fiscal Years commencing on or after 1 January 2025, when each of those provisions of the Assessment Bill take effect. [Table item 1 in subsection 2(1) of the Imposition Bill]

Chapter 2: Taxation (Multinational - Global and Domestic Minimum Tax) Bill 2024

Outline of chapter

2.1 This Chapter explains the operation of the Taxation (Multinational—Global and Domestic Minimum Tax) Bill 2024 (Assessment Bill).

2.2 The Assessment Bill establishes a new taxation framework to implement the GloBE Rules and an Australian DMT for certain MNE Groups. The framework establishes rules for assessing the global and domestic minimum top-up tax liabilities of certain MNEs as a part of a coordinated global approach. The Assessment Bill ensures that MNEs within scope of the GloBE Rules have an ETR of at least 15 per cent in respect of the GloBE income arising in each jurisdiction in which they operate, consistent with the GloBE Rules.

Summary of new law

2.3 The Assessment Bill sets out a framework for the entities that are liable to top-up tax in a way that seeks to achieve outcomes consistent with the GloBE Rules. This includes establishing the entities that are within scope of the GloBE Rules, relevant definitions that are used to support the framework and the description of taxes that may be charged to an entity. A list of defined terms and their definitions is included at Error! Reference source not found. .

2.4 It is intended that the substantive computation of top-up tax, consistent with the GloBE Rules, is to be determined via Rules made under the Minister's rule-making power. This approach ensures that future Agreed Administrative Guidance released by the OECD can be more readily incorporated into the Australian regime in a timely and efficient manner, while retaining an appropriate level of parliamentary oversight. This Bill contains empowering provisions to ensure such Rules can sufficiently provide the requirements for computing an ETR. Provisions consistent with the ancillary Chapters 6 and 7 of the GloBE Rules are intended to be contained in the Rules to support the ETR computations for special entities. The safe harbours and transitional provisions from Chapters 8 and 9 of the GloBE Rules are intended to be contained in the Rules.

Detailed explanation of new law

Objective

2.5 The objective of the Assessment Bill is to ensure MNE groups pay a minimum level of tax on the income arising in each of the jurisdictions where they operate. It does so by imposing top-up tax on profits made in a jurisdiction whenever the ETR, that is determined for that jurisdiction, is below the 15 percent global minimum rate.

2.6 The Assessment Bill provides the framework for the imposition of these minimum taxes, namely Australian IIR tax, Australian DMT tax and Australian UTPR tax. It sets out the entities, groups and other arrangements that are within scope of such taxes, as well as providing for entities that are excluded from the minimum tax regime. This framework is designed to be wholly consistent with the GloBE Rules to ensure Australia plays its part in the coordinated global approach to combat multinational tax avoidance being led by the OECD.

2.7 Collection mechanism, lodgment and secondary liability provisions, including instances where other entities in the MNE Group are jointly and severally liable for such top-up taxes, are included in Schedule 1 to the TAA. Further explanation of these provisions is provided in Chapter 3:.

Liability to tax

2.8 The starting point for the imposition of Australia's global and domestic minimum taxes is provided in the Assessment Bill, which provides that tax is payable by entities with a 'top-up tax amount'. Specifically, this Bill provides that the following tax is payable by an Entity if the Entity has a 'top-up tax amount' for the Fiscal Year:

- •

- Australian DMT tax equal to the sum of its Domestic Top-up Tax Amounts;

- •

- Australian IIR tax equal to the sum of its IIR Top-up Tax Amounts; and

- •

- Australian UTPR tax equal to the sum of its UTPR Top-up Tax Amount.

The meaning of Entity is discussed at paragraph 2.27 below. [Sections 6, 8 and 10 of the Assessment Bill]

2.9 To ensure Australia's framework is sufficiently flexible, the meaning of top-up tax amount for each of these top-up taxes is delegated to the Rules. This flexibility is necessary to ensure that Australia is best placed to accommodate internationally agreed developments in a timely and efficient manner, while still retaining sufficient parliamentary oversight of our domestic law. [Sections 7, 9 and 11 of the Assessment Bill]

2.10 The imposition of Australian DMT tax allows Australia to collect additional tax on excess profits of Constituent Entities of MNE Groups located in Australia in order to bring the ETR up to the 15 per cent minimum rate.

2.11 Australian IIR tax is to be imposed on certain parent entities of MNE Groups that are within scope of the Minimum Tax law in respect of undertaxed profits of Constituent Entities within the MNE Group that operate in low-tax jurisdictions.

2.12 Where a jurisdiction, that has the right to impose IIR top-up tax in respect of another jurisdiction's low-tax income, does not exercise that right, top-up tax is collected by all jurisdictions that have implemented a UTPR top-up tax regime. In accordance with the GloBE Rules, the total amount of top-up tax is allocated among jurisdictions by reference to a substance-based allocation key. Implementing jurisdictions can collect the top-up tax by applying the UTPR top-up tax as a denial of deduction under its existing corporate income tax, or through an equivalent mechanism. In Australia, an equivalent mechanism rather than a denial of deduction is to be adopted.

Group, MNE Group and Applicable MNE Group

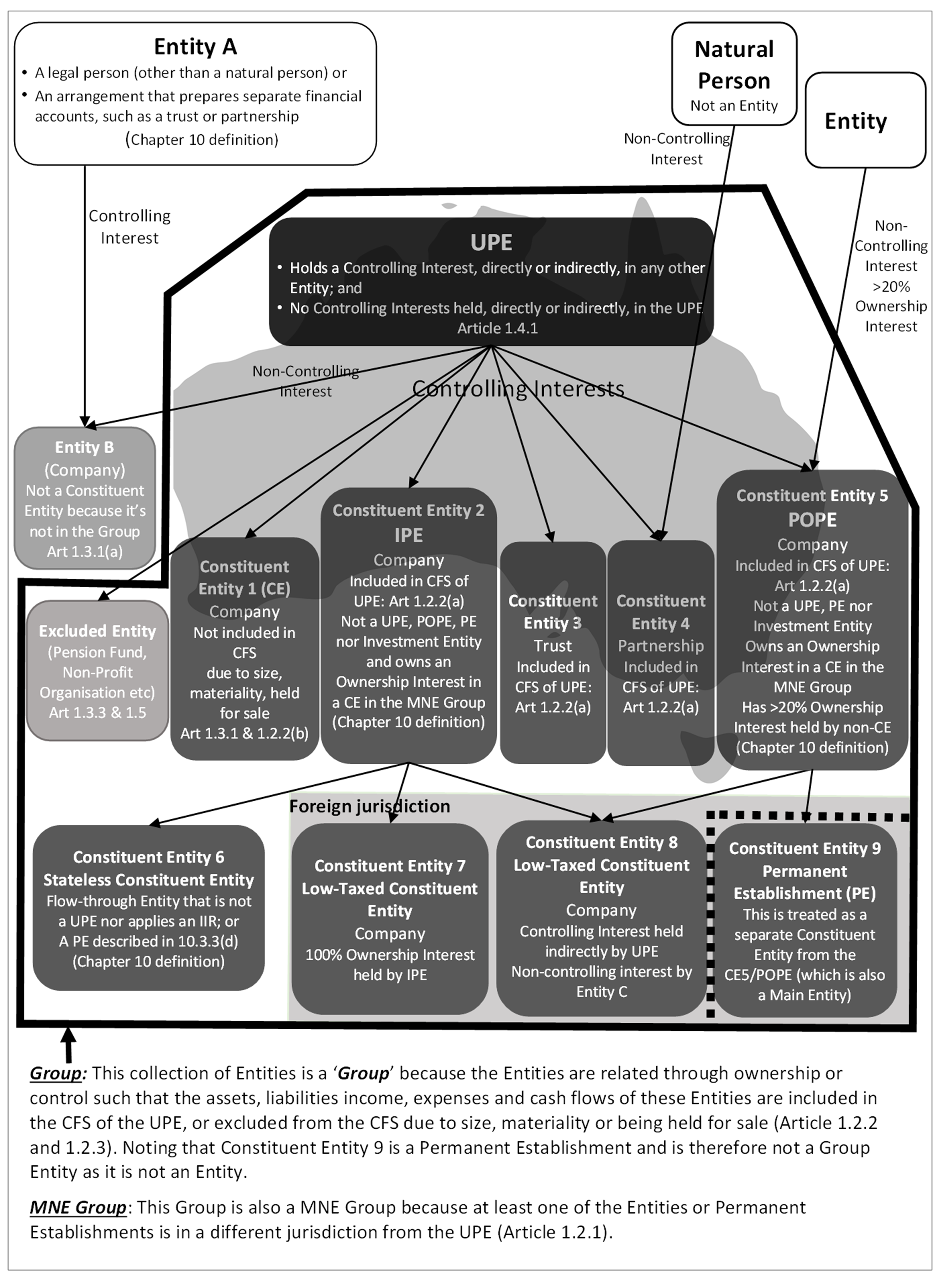

2.13 Top-up tax computations are applicable to a MNE Group that satisfies the GloBE Threshold (see from paragraph 2.19 below for an explanation of this term). An MNE Group consists of a Group that includes at least one Entity or Permanent Establishment that is not located in the jurisdiction of the UPE of the Group. A Group, broadly, refers to the UPE and all those Entities related through ownership or control with the UPE, whose assets, liabilities, income, expenses and cashflows are consolidated in the financial statements of the UPE, or are excluded from the UPE's Consolidated Financial Statements due to the Entity's size, being immaterial or being held for sale. Each of these Entities is referred to as a Group Entity and provided the Entity is not an Excluded Entity, it is a Constituent Entity of the MNE Group. The meaning of an Entity is explained from paragraph 2.27 below and the meaning of a Constituent Entity is explained at paragraph 2.31 below. [Sections 14, 15 and 17 of the Assessment Bill]

2.14 Each Entity that is excluded from the CFS of the UPE solely due to their size or materiality or that are held for sale are treated as part of the Group.

2.15 Where a Group consists of multiple Group Entities, any of those Group Entities that carries on business at or through a Permanent Establishment in one or more other jurisdictions and includes the Financial Accounting Net Income or Loss of those Permanent Establishments in its financial statements, is the Main Entity in respect of those Permanent Establishments. Provided the Main Entity is not an Excluded Entity, those Permanent Establishments are Constituent Entities, separate from the Main Entity and from each other Permanent Establishment. While the Main Entity is a Group Entity, those Permanent Establishments are not Group Entities as they are not Entities. [Subsections 17(1), 18(1) to (3) and 19(1) and (2) and 20 of the Assessment Bill]

2.16 The term MNE Group also extends to a single Main Entity together with its Permanent Establishments. A Main Entity in respect of one or more Permanent Establishments that are located in other jurisdictions, is treated as a Group, with each Permanent Establishment and the Main Entity being separate Constituent Entities of an MNE Group, provided the Main Entity is not an Excluded Entity. [Subsections 14(1), 18(4) 19(1) and 19(2) and paragraphs 14(2)(b), 15(b), 16(1)(b) of the Assessment Bill]

2.17 While, for the purposes of this Assessment Bill, Permanent Establishments are treated as Constituent Entities, separate from the Main Entity and separate from any other Permanent Establishment of the Main Entity, these deeming rules create a legal fiction, that is unique to this taxation framework, to implement the GloBE Rules and a DMT for certain MNE Groups. It has no impact on any other Australian taxation laws. The concept of a Permanent Establishment being a Constituent Entity is also not relevant for the purposes of the TAA.

2.18 An MNE Group subject to the Minimum Tax law is called an Applicable MNE Group. A MNE Group will be an Applicable MNE Group for a Fiscal Year if, for at least 2 of the 4 Fiscal Years immediately preceding that year, the annual revenue of the MNE Group shown in the Consolidated Financial Statements of the UPE is at least EUR 750 million. Where any of those preceding Fiscal Years is less than a 12-month period, the annual revenue amount is pro-rated on a monthly basis. If the annual revenue is expressed in a currency other than EUR, it must be translated to EUR in accordance with the relevant currency translation method provided in the Rules. [Subsections 12(1), (2) and (4) of the Assessment Bill]

2.19 The consolidated annual revenue of the MNE Group is referred to as the GloBE Threshold. The EUR 750 million GloBE threshold includes revenue from any Excluded Entities in the MNE Group and income from international shipping as well as the portion of revenue from Joint Operations consolidated in the CFS of the UPE. [Subsections 12(2) and (3) of the Assessment Bill]

2.20 The annual revenue of the MNE Group is the amount determined in accordance with relevant accounting standards that represents the amount disclosed in the CFS as annual revenue of the MNE Group, which may allow for netting of discounts, returns and allowances, which are generally reflected in the profit and loss statement. Revenue amounts include the inflow of economic benefits arising from delivering or producing goods, rendering services, or other activities that constitute the MNE Group's ordinary activities. All MNE Groups must include net gains from investments (whether realised or unrealised) reflected in the profit and loss statement of the CFS and income or gains separately presented as extraordinary or non-recurring items. [Subsection 12(2) of the Assessment Bill]

2.21 Where an MNE Group's consolidated profit and loss statement presents gross gains from investments and gross losses from investments separately, then the MNE Group must reduce revenues by the amount of such gross losses to the extent of gross gains from investments in determining revenues for the GloBE threshold.

2.22 For financial entities, which may not record gross amounts from transactions in their financial statements with respect to certain items, the item(s) considered similar to revenue under the UPE's financial accounting standards should be used in the context of financial activities. Those items could be labelled as 'net banking product', 'net revenues', or others depending on the financial accounting standard. For example, if the income or gains from a financial transaction, such as an interest rate swap, is appropriately reported on a net basis under the UPE's financial accounting standards, the term 'revenue' means the net amount from the transaction.

2.23 Where the UPE does not prepare a CFS, the CFS of the UPE are instead those that would have been prepared if such Entity were required to prepare such statements in accordance with an Authorised FAS adjusted for Material Competitive Distortions. [Definition of Consolidated Financial Statements in section 34 of the Assessment Bill]

2.24 The Rules are intended to prescribe how to translate other currencies into Euros for the purposes of determining whether the GloBE Threshold is met or exceeded. [Subsections 12(3) and (4) of the Assessment Bill]

2.25 The GloBE Rules outline relevant guidelines regarding the GloBE Threshold for mergers and acquisitions. Therefore, the Assessment Bill empowers conditions for being an Applicable MNE Group to be specified in the Rules. [Paragraph 12(1)(b) of the Assessment Bill]

2.26 Diagram 2.1 illustrates the concepts of an MNE Group and a Group. Relevantly, a Permanent Establishment is not an Entity, but is deemed to be a Constituent Entity of the MNE Group and a Group Entity separate from the Main Entity. As noted in the diagram, the Group is also a MNE Group because at least one of the Entities or Permanent Establishments is in a different jurisdiction from the UPE. [Subsection 14(1) of the Assessment Bill]

Diagram 2.1

Entities

2.27 An Entity is any legal person (other than a natural person). To ensure partnerships, trusts and other arrangements are captured, the definition of Entity also extends to an arrangement that prepares separate financial accounts. Given the reliance on the CFS, each Entity can only be in one MNE Group consolidated on a line-by-line basis. [Subsections 13(1) and (2) of the Assessment Bill]

UPE

2.28 A UPE is either a sole Main Entity, which is deemed to be a Group with its Permanent Establishments in other jurisdictions, or an Entity which satisfies both of the following:

- •

- it directly or indirectly holds a Controlling Interest in another Entity; and

- •

- no Controlling Interest in it is held directly or indirectly by another Entity. [Subsections 13(3) and 18(4) of the Assessment Bill]

2.29 The terms 'Controlling Interest' and 'Ownership Interest' are used for different purposes within the GloBE Rules. In general, where a UPE holds a Controlling Interest in another Entity, the UPE will consolidate the Entity's assets, liabilities, income, expenses and cash flows, on a line-by-line basis, into its CFS pursuant to the Acceptable FAS. The Main Entity in respect of one or more Permanent Establishments is deemed to hold a Controlling Interest in each Permanent Establishment. [Paragraph 18(2)(b) and subsection 38(4) of the Assessment Bill]

2.30 In contrast, an Ownership Interest is any equity interest that carries rights to the profits, capital or reserves of an entity, including the profits, capital or reserves of a Main Entity's Permanent Establishment. Ownership Interest is used for the purposes of determining a Parent Entity's Allocable Share of top-up tax. [Paragraph 38(1)(a) and subsections 38(4) and 39(5), (6) and (7) of the Assessment Bill]

Constituent Entity

2.31 A Constituent Entity is an Entity that is included in the MNE Group and is not an Excluded Entity. A Permanent Establishment is deemed to be a Constituent Entity so that it is captured within the MNE Group and subject to top-up tax. An Excluded Entity is not a Constituent Entity. [Section 16, subsection 17(4) and paragraph 18(4)(b) of the Assessment Bill]

Permanent establishments and main entities

2.32 A Permanent Establishment is a place of business (including a deemed place of business) of the Main Entity, carried on in a jurisdiction other than where the Main Entity is located, and where the income attributable to that Permanent Establishment is taxed in that jurisdiction in accordance with the Business Profits Article, or similar provision, of an applicable Tax Treaty or on a net basis under the income tax laws of that jurisdiction. If a jurisdiction has no corporate income tax system, a place of business (including a deemed place of business) is a Permanent Establishment if the jurisdiction would have had a right to tax the income attributable of that place of business in accordance the Business Profits Article of the OECD Model Tax Convention. Where none of these definitions are satisfied, a place of business (including a deemed place of business) is also a Permanent Establishment if such business operations are conducted outside the jurisdiction where the Main Entity is located and the income attributed to those operations is exempt from income tax in that jurisdiction. [Subsection 19(1) of the Assessment Bill]

Example 2.1 There is an applicable tax treaty in force

A Constituent Entity resident in Country R is dedicated to the operation of aircraft in international traffic and has an office in Country S through which it carries on part of its business. Assume that the R-S treaty follows the OECD Model Tax Convention. In accordance with Article 5 of the treaty, this Constituent Entity has a Permanent Establishment in Country S. However, by virtue of Article 7(4) and Article 8 of the OECD Model Tax Convention, Country S is not able to tax the profits of the Permanent Establishment. In that case, a Permanent Establishment does not exist for purposes of the Minimum Tax law in accordance with section 19 of the Assessment Bill, regardless of the fact that it meets the definition of a Permanent Establishment of the treaty. [Subsection 19(1)(a) of the Assessment Bill, Commentary p.209-210 para 97-102]

Example 2.2 Where there is no applicable tax treaty in force a Permanent Establishment can be recognised under domestic law:

A Co and B Co are Constituent Entities resident in foreign Country A and B respectively, and the sole partners of a partnership in Australia. There is no Tax Treaty in force between Country A and Australia, nor Country B and Australia. Under the domestic law of Australia, the partnership is considered as tax transparent, and A Co and B Co are taxed on their share of the income attributed to the partnership on a net basis in Australia. In this case, paragraph 19(1)(b) of the Assessment Bill recognises the existence of two Permanent Establishments as two separate Constituent Entities. [Paragraph 19(1)(b) of the Assessment Bill, Commentary p.210 para 103-107]

Example 2.3 A Permanent Establishment can be recognised in a country with no corporate income tax system

An Australian resident carries on business in Country X, a jurisdiction with no corporate income tax system. As Country X has no corporate income tax system, a hypothetical analysis is required to determine whether the Australian resident's place of business in Country X is a Permanent Establishment for the purposes of the Minimum Tax law. On the assumption that a Tax Treaty, that replicates the last version of the OECD Model Tax Convention, exists between Australia and Country X, the place of business would not satisfy the definition of Permanent Establishment under that treaty. However, in a later year, the OECD Model Tax Convention is amended such that the place of business satisfies the definition of permanent establishment under the treaty and Country X would have a right to tax the income attributable to those business operations. In this later Fiscal Year, the Australian resident is taken to have a Permanent Establishment in Country X for the purposes of the Minimum Tax law. [Paragraph 19(1)(c) of the Assessment Bill, Commentary p.210-211, para 108-110]

Example 2.4 A Permanent Establishment can be recognised where the income attributed to business operations is exempt in the residence jurisdiction

A Co is located in Australia and conducts activities in jurisdiction B through a person that habitually concludes contracts in the name of A Co. Jurisdiction B has adopted the definition of a Permanent Establishment of Article 5 of the OECD Model Tax Convention into its domestic law and taxes the income attributable to it. The income attributable to those business operations is exempt from income tax in Australia under the foreign branch exemption in section 23AH of the ITAA 1936. Australia and Jurisdiction B have not entered into a bilateral Tax Treaty. In this case, paragraph 19(1)(b) is satisfied because jurisdiction B taxes the income attributable to a Permanent Establishment in accordance with its domestic law. While paragraph 19(1)(d) is also satisfied because Australia exempts the income attributable to those operations, it does not apply because a Permanent Establishment is recognised under paragraph 19(1)(b). If, however, jurisdiction B does not treat an agent that habitually concludes contracts in the name of its principal as giving rise to a Permanent Establishment under local law then paragraph 19(1)(d) would apply, but the Permanent Establishment would be stateless, and treated on a standalone basis, for the purposes of the Minimum Tax law without the ability to blend the income attributed to the Permanent Establishment with other Constituent Entities located in jurisdiction B. [Paragraphs 19(1)(b) and (d) of the Assessment Bill, Commentary p.211-212, para 111-114]

2.33 For the purposes of paragraph 19(1)(d) of the Assessment Bill, "operations are conducted outside the jurisdiction" can be interpreted to also mean "activities conducted outside the jurisdiction". [Paragraph 19(1)(d) of the Assessment Bill]

Joint Ventures

2.34 JV arrangements, where a UPE of an MNE Group holds at least 50% of the ownership interests in an Entity (directly or indirectly) and the financial results of the Entity are reported under the equity method in the CFS of the UPE for the Fiscal Year, are subject to the Minimum tax law and top-up tax where any of profits of the JV Group are undertaxed. In this case, the Entity is a JV of the MNE Group. [Subsection 26(1) of the Assessment Bill]

2.35 A JV of an MNE Group does not include a UPE of an Applicable MNE Group. This precludes the UPE of one MNE Group that accounts for a UPE of a second MNE Group under the equity method in its CFS and holds an Ownership Interest Percentage in that second UPE of at least 50%. This avoids treating a UPE of an MNE Group that is already subject to the Minimum Tax law as a JV of another MNE Group and therefore, potentially subject to taxation by two jurisdictions (once as a standalone MNE Group and another to the second MNE Group). [Subsection 26(2) of the Assessment Bill]

2.36 An Entity is not a JV if it is an Excluded Entity, or the Ownership Interests in the Entity held by the MNE Group are held directly by an Excluded Entity or held indirectly through Excluded Entities. [Subsection 26(2) of the Assessment Bill]

2.37 A JV Group consists of the JV and its JV Subsidiaries. A JV Subsidiary include any Entity whose assets, liabilities, income, expenses and cash flows are consolidated by the JV under an Acceptable Financial Accounting Standard, or would have been had the JV been required to under that Standard. A JV Subsidiary is excluded from being a JV. [Paragraph 26(2)(e) and section 27 of the Assessment Bill]

2.38 In determining whether an Entity is a JV, the reference to Indirect Ownership Interests 'held through' an Excluded Entity is intended to cover situations where there are multiple Excluded Entities interposed between the UPE of the MNE Group and the Entity. It covers situations where an Excluded Entity of the MNE group holds a Direct Ownership Interest in an Entity and the activities conducted by the Entity either satisfies the 'Activities Test' (see from paragraph 2.59 below for an explanation of the Activities Test) or a description as prescribed by the Rules. [Paragraph 26(2)(c) and subsections 38(1), (2) and (5) of the Assessment Bill]

2.39 The GloBE Rules require top-up tax of JVs and JV Subsidiaries to be calculated separately from the MNE Group. It is intended that the Rules will prescribe for the computation of top-up tax of the JV separately from MNE Group to ensure that the GloBE income or loss and covered taxes of the JV and JV Subsidiaries are not combined with the Constituent Entities of the broader MNE Group. [Paragraph 33(1)(j) of the Assessment Bill]

Multi-Parented MNE Groups

2.40 The GloBE Rules stipulate special rules that apply for Multi-Parented MNE Group. To provide for those special rules, section 28 of the Assessment Bill provides an empowering provision for the Rules to set out the manner in which the Assessment Bill applies in relation to such MNE Groups. The Rules are intended to provide a definition of Multi-Parented MNE Group. In the event of any inconsistency between the Assessment Bill and the Rules, the Assessment Bill applies subject to the Rules. [Section 28 and definition of Multi-Parented MNE Group in section 34 of the Assessment Bill]

2.41 This empowering provision is necessary to ensure sufficient flexibility and adaptability in the Minimum Tax law to accommodate the requirements of the OECD Two-Pillar Solution. Failing compliance with such requirements may put at risk the qualifying status of Australia's Minimum Tax law, contrary to the intended policy outcome to contribute to the global approach to combat multinational tax avoidance and to ensure protection of Australian taxing rights under this approach.

Excluded Entity

2.42 The GloBE Rules stipulate that an Excluded Entity is not subject to the GloBE Rules. The Assessment Bill prescribes, consistent with the GloBE Rules, the definition of an Excluded Entity. However, the revenue of an Excluded Entity is included in ascertaining whether the EUR 750 million GloBE Threshold has been satisfied. [Sections 12 and 20 of the Assessment Bill]

2.43 Excluded Entities who are Group Entities of an MNE Group are excluded from being Constituent Entities of an MNE Group. A subsidiary of an Excluded Entity that is not an Excluded Entity itself is not an Excluded Entity. [Subsection 17(4) of the Assessment Bill]

2.44 The following entities are defined as Excluded Entities:

- •

- a Governmental Entity;

- •

- an International Organisation;

- •

- a Non-profit Organisation;

- •

- a Pension Fund;

- •

- an Investment Fund that is an UPE;

- •

- a Real Estate Investment Vehicle that is an UPE;

- •

- an Excluded Service Entity; and

- •

- an Entity prescribed by the Rules. [Subsection 20(1) of the Assessment Bill]

2.45 If a Main Entity is an Excluded Entity, the Permanent Establishment is also treated as an Excluded Entity for the purposes of the Assessment Bill. This deeming does not result in the Permanent Establishment being treated as an Entity for the purposes of the Assessment Bill. [Subsections 20(2) and (3) of the Assessment Bill]

Sovereign wealth funds and Government Entities

2.46 Sovereign wealth funds are commonly established by governments to hold or manage investments on behalf of the government or jurisdiction. A sovereign wealth fund which meets the definition of a Governmental Entity, such as Australia's Future Fund, cannot be a UPE and will not be considered part of an MNE Group. Because some sovereign wealth funds can hold a controlling interest in another Entity, it is possible for an Entity to be controlled by a sovereign wealth fund and included in the CFS of a sovereign wealth fund. This specific exclusion ensures that such a sovereign wealth fund cannot be a UPE of an MNE Group. [Subsections 13(3), 21(2) and section 18 of the Assessment Bill]

2.47 Generally, an Excluded Entity can be a UPE if it holds a controlling interest in another Entity. However, where the Excluded Entity is a Government Entity, it will not be a UPE. This is because Government Entities are not typically required to consolidate the financial results of non-Government Entities they own on a line-by-line basis. This is also because the term Entity does not include central, state, or local government or their administration or agencies that carry out government functions. [Section 13 and definition of Controlling Interest in section 34 of the Assessment Bill]

2.48 An Entity that is wholly or partially owned by a government is a Governmental Entity if:

- •

- the principal purpose of the Entity is to either fulfill a government purpose or to manage or invest the government's assets, and the Entity does not engage in any other trade or business;

- •

- it is accountable on its overall performance, and provides annual reporting information, to the government; and

- •

- its assets vest in the government upon dissolution and any distributions of net earnings are made solely to the government. [Subsection 21(1) of the Assessment Bill]

International Organisations and Non-profit Organisations

2.49 Similar to Governmental Entities, International Organisations are Excluded Entities for the purposes of the Minimum Tax law. International Organisations include organisations that are comprised primarily of governments, are subject to privileges and immunities in those jurisdictions and its income is precluded from benefitting private persons. In addition, a subsidiary of such an organisation is also an International Organisation provided its income is also precluded from benefitting private persons. [Subsection 22(1) of the Assessment Bill]

2.50 A Non-profit Organisation is also an Excluded Entity on the basis that it is established exclusively for religious, charitable scientific, artistic, cultural, athletic, educational or other similar purposes or for the promotion of social welfare and substantially all of its income from its operations is exempt from tax in the jurisdiction in which it is created and managed. It is precluded from carrying on any trade or business apart from that directly related to the purpose for which the Organisation is established. It must not have any shareholders or members with a proprietary interest in its income or assets nor can its income benefit private persons or a non-charitable Entity apart from providing benefits, or compensation for services rendered or property purchased, as part of its ordinary operations. Upon winding up, all of its assets must be distributed or diverted to the government or a Non-profit Organisation. [Subsection 22(2) of the Assessment Bill]

Pension Funds and Pension Services Entity

2.51 The definition of Pension Fund aligns with the definition of 'recognised pension fund' in the OECD Model Tax Convention but does not require the Fund to be taxable as a separate person in the jurisdiction of formation so as to cater for trusts. A Pension Fund is a government-regulated Entity established exclusively, or almost exclusively, for the purpose of administering and providing retirement-type benefits to individuals. The government regulation must provide for the protection of such benefits and a protected pool of assets must secure the funding of those corresponding pension obligations. [Subsection 23(1) of the Assessment Bill]

2.52 It is generally expected that an Australian complying superannuation fund (within the meaning of complying superannuation fund in section 45 of the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993) would meet the definition of Pension Fund.

2.53 Similar to the OECD Model Tax Convention, a Pension Services Entity is an Entity or a group of such Entities, that alone or together, are established and operated exclusively, or almost exclusively, to invest funds for the benefit of Pension Funds. [Subsection 23(2) of the Assessment Bill]

Real Estate Investment Vehicles and Investment Funds

2.54 A Real Estate Investment Vehicle is a separate category of an Excluded Entity, that must satisfy three conditions, being that it is widely held, it holds predominantly immovable property and it achieves a single level of taxation, either in the hands of the vehicle or its equity interest holders. This definition of real estate investment vehicle draws on the "special tax regime" provision included in the Commentary on Article 1 of the OECD Model Tax Convention. [Subsection 24(1) of the Assessment Bill]

2.55 An Investment Fund is an Entity that:

- •

- is designed to pool financial and non-financial assets of investors, some of whom are not connected;

- •

- has, and invests in accordance with, a defined investment policy;

- •

- allows its investors to reduce transaction, research and analytical costs or to spread risk collectively;

- •

- is designed to either generate investment income or gains, rather than operating income, such as dividends, interest, rent, returns from other Investment Funds and capital gains, or to protect against a specific event or outcome, such as in the insurance industry;

- •

- entitles its investors to a right of return based on their contributions;

- •

- is, or the fund manager is, subject to a prudential regulatory regime in the jurisdiction in which the fund is established or managed;

- •

- is managed by investment fund management professionals, such as independent fund managers that are subject to a national fund-management regulatory regime and whose compensation for services rendered to the fund is partly based on the performance of the fund. [Subsection 24(2) of the Assessment Bill]

2.56 The definition of investment fund requires that at least some investors are not connected, which is determined based on a facts and circumstances test. Individual investors are connected if they are 'closely related' to another investor in accordance with paragraph 8 of Article 5 of the OECD Model Tax Convention or are part of the same family including a spouse or de facto partner, siblings, parents, and ancestors and lineal descendants such as grandparents and grandchildren. [Subsections 24(3) and (4) of the Assessment Bill]

Excluded Service Entity

2.57 An Entity can be an Excluded Service Entity depending on the value of the Entity owned by Excluded Entities, other than a Pension Services Entity, and the activities conducted by the Entity satisfy what the GloBE Rules refer to as the 'Activities Test' (see from paragraph 2.59 below for an explanation of the Activities Test).

2.58 The 'value of the Entity' refers to the aggregate value of the Ownership Interests held by the Excluded Entity in the Entity as a percentage of the overall value of the Ownership Interests issued by the Entity. This should be tested on the date of the most recent change in the Excluded Entity's relative Ownership Interests in the Entity and should take into account all Ownership Interests held by the Excluded Entity. Unrealised movements in the comparative value between different class of shares should not affect the application of this test. [Paragraph 25(a) of the Assessment Bill]

Example 2.5

Base case: Value of entity

A newly formed Entity issues 200 ordinary shares worth EUR 1 each and 100 preferred shares worth EUR 2 each.

An Excluded Entity shareholder receives all the ordinary shares and 90 of the preferred shares.

The value of the Entity would be 400 and the Excluded Entity shareholder owns 95% (380/400) of the value of the Entity.

Modification: Value of ownership interests decrease

If the value of the Ownership Interests of the Entity fell to 300 such that the ordinary shares are now worth only 100, the Excluded Entity should still be treated as holding 95% of the value of the Entity despite the fact that the total market value of its shares is 93% (280/300) of the Entity as a whole.

2.59 An Excluded Service Entity must have at least 95 per cent of its value owned by Excluded Entities and meet one, or both, of the following criteria, which is referred to in the GloBE Rules as the Activities Test:

- •

- the Entity operates exclusively or almost exclusively to hold assets or invest funds for the benefit of the Excluded Entities; and

- •

- the Entity only carries out activities that are ancillary to those carried out by the Excluded Entities. [Paragraph 25(b) of the Assessment Bill, Commentary p.22 para 52-56]

2.60 The words "exclusively or almost exclusively" denote a facts and circumstances test that requires all or almost all of the Entity's activities to be related to holding assets or investing funds. This precludes Entities that might be wholly-owned, or almost wholly-owned, by an Excluded Entities, but that carry on commercial business operations. In this case, because the Entity carries on commercial business activities that go beyond holding assets or investing funds, that Entity would not satisfy the Activities Test. [Subparagraph 25(b)(i) of the Assessment Bill, Commentary p.22 para 53]

Alternatively, the Activities Test is also met if the Entity only carries out activities that are ancillary to the activities carried out by the Excluded Entities that hold Ownership Interests in the Entity (other than a Pension Service Entity). Where the Entity carries on such ancillary activities in addition to other activities, provided those other activities fall within the first limb of the Activities Test, the Entity will be an Excluded Services Entity. [Subparagraphs 25(b)(i) and (ii) of the Assessment Bill]

2.61 This rule applies to Excluded Service Entities that are Permanent Establishments. Where an Entity meets the definition of an Excluded Entity based on the totality of the activities of the Entity, any activities undertaken by its Permanent Establishment are not considered separate when applying the Activities Test. Where a Main Entity meets the definition of an Excluded Entity, its Permanent Establishment will also be an Excluded Entity (noting that this deeming does not mean that the Permanent Establishment is an Entity or a Group Entity). [Subsections 20(2) and (3) of the Assessment Bill]

2.62 For an Entity that is considered to be an Excluded Service Entity, a Filing Constituent Entity can make a Five-Year Election not to treat that Entity as an Excluded Entity. If an election is made, the Entity would be treated as a Constituent Entity and not an Excluded entity. [Subsections 20(4) to (6) of the Assessment Bill]

2.63 If an election is made, it will be a Five-Year Election, which means that it cannot be revoked with respect to a Fiscal Year (election year) or the four succeeding years immediately after the election year. The election will remain in effect indefinitely until it is revoked with respect to a Fiscal Year (the revocation year), from which point the MNE Group cannot make another election for the four succeeding years immediately after the revocation year. [Section 36 of the Assessment Bill]

2.64 It is intended for MNE Groups to be able to make an election to treat an Entity as not being an Excluded Entity so that Australian IIR tax can apply in respect of Constituent Entities in other low-tax jurisdictions and therefore preclude UTPR top-up tax being imposed in respect of that Constituent Entity. [Subsections 20(4) and (5) of the Assessment Bill]

Ownership interests

2.65 Both direct and indirect Ownership Interests are taken into account when determining which Entities are within scope of the Minimum Tax law. Direct Ownership Interests are broadly defined as interests that carry rights to the share of profits, capital and/or reserves in an Entity and that would be classified as equity under the relevant financial accounting standard. The relevant financial accounting standard is the financial accounting standard used in the preparation of the relevant CFS. [Subsections 38(1) and (2) of the Assessment Bill]

2.66 The Rules may prescribe that an interest is not a Direct Ownership Interest in an entity. This is a necessary and appropriate function for the Rules in the event future Agreed Administrative Guidance is released which would enable Australia to maintain consistency with the GloBE Rules. [Subsections 38(3) of the Assessment Bill]

Example 2.6 Ownership interests

a. Identifying whether an indirect ownership interest exists

Scenario A: Entity A holds a Direct Ownership Interest in Entity B. Entity B holds a Direct Ownership Interest in Entity C.

Outcome: Therefore, Entity A holds an Indirect Ownership Interest in Entity C. [Subsection 38(5) of the Assessment Bill]

b. Calculating the proportion of a direct ownership interest

Scenario B: Entity A issues ownership interests of two types, profit units which carry equal rights to the profits of the entity and capital units which carry equal rights to the capital of the entity in liquidation. These units are held by 3 other entities, B, C and D. Entity B holds 50% of the issued profit units and 80% of the issued capital units. Entity C holds 50% of the profit units. Entity D holds the remaining 20% of capital units.

Outcome: Entity B's ownership interest amounts to the average of its ownership interests in Entity A:

Entity C has 25% of the ownership interest in A:

Entity D has the remaining 10%:

[Subsections 39(1) and (2) of the Assessment Bill]

c. Calculating the proportion of an indirect ownership interest

Scenario C: Entity A directly owns 70% of the shares in Entity B which directly owns 40% of shares in Entity C.

Outcome: Entity A has an indirect ownership interest of 28% in Entity C, held through Entity B:

[Subsections 39(1) and (2) of the Assessment Bill]

Interpretation

2.67 The provisions of the Assessment Bill, including the Rules made for the purposes of provisions under the Assessment Bill, are to be interpreted in a manner consistent with the GloBE Rules, Commentary, Agreed Administrative Guidance, Safe Harbour Rules, and a document, or part of a document prescribed by the Rules. This does not affect the application of section 15AB of the Acts Interpretation Act 1901. [Subsections 3(1), (3) and (5) of the Assessment Bill]

2.68 This interpretation is necessary because the effectiveness of the GloBE Rules depends on a coordinated global common approach. This means that OECD Inclusive Framework members are not required to adopt the GloBE rules. But, if they choose to do so, then they:

- •

- must implement and administer the rules in a way that is consistent with the Model Rules and Guidance agreed to by the OECD Inclusive Framework; and

- •

- must accept the application of the GloBE Rules applied by other OECD Inclusive Framework members including agreement as to rule order and the application of any agreed safe harbours.

2.69 Such alignment and consistency is being enforced through an OECD Inclusive Framework Peer-Review Process.

2.70 The Rules may also prescribe that a document or part of a document be disregarded in interpreting the Assessment Bill. This provides for the circumstances where it is necessary to interpret a provision of the Assessment Bill in a manner that is inconsistent with parts of a document. It can also be used to resolve inconsistencies between documents for the purposes of interpreting the Assessment Bill. [Subsection 3(2) of the Assessment Bill]

2.71 The provisions of the Assessment Bill and the Rules also use common financial accounting terms that are not defined. When principles that rely on financial accounting, or financial accounting terminology or concepts that are not defined are used, such terms and concepts should be interpreted consistently with the meaning given to them in financial accounting standards and guidance.

2.72 The GloBE Rules, Commentary and Agreed Administrative Guidance published by the OECD are defined with reference to their full titles. [Subsection 3(4) of the Assessment Bill]

Rule-making powers

2.73 The Minister may, by legislative instrument, make Rules related to computation of top-up tax. [Sections 29 and 33 of the Assessment Bill]

2.74 This Rule making power has been included to ensure that any OECD Administrative Guidance can be incorporated efficiently and in a timely manner, while still retaining an appropriate level of parliamentary oversight. The Rules are subject to disallowance, which will enable Parliament to exercise control over the legislative power delegated to the Minister.

2.75 The Rules may, via reference, incorporate extrinsic materials in force at the time the Rules are made at a fixed point in time. However, this is limited to the extent that it is consistent with the approved OECD documents, such as Agreed Administrative Guidance. [Section 31 of the Assessment Bill]

2.76 This is appropriate given that the GloBE Rules are designed to provide for a coordinated system of taxation in the global and digitalised economy and intended to be implemented as part of a global common approach. The release of any OECD Agreed Administrative Guidance or other official documents related to the Two-Pillar solution are freely available from the OECD website.

2.77 If a legislative instrument or notifiable instrument, or a provision of such an instrument, commences before the instrument is registered, the instrument implementing the Rules may apply from the time of commencement, rather than the time of registration. This is necessary to ensure consistency with the GloBE Rules to maintain qualified status. The Rules are limited in that they are not able to modify or prescribe the operation of the Assessment Bill. However, in the event of ambiguity in the interpretation of the legislative instruments, the meaning prescribed by the Rules shall prevail. [Section 32 of the Assessment Bill]

2.78 The Rules may confer a power or function relating to the operation, application, or administration of the Rules, which may be exercised via a legislative instrument or notifiable instrument. However, only the Minister may make a legislative instrument in the Rules, which cannot be delegated. Similarly, only the Minister, Secretary or Commissioner may make a notifiable instrument, which can only be delegated to an SES employee within the Department or the ATO. This delegation is appropriate as the SES will have the relevant experience and expertise in making a notifiable instrument, should the need arise. [Section 30 of the Assessment Bill]

2.79 Subsection 12(3) of the Legislation Act 2003 allows legislative instruments to apply retrospectively if the enabling legislation expressly provides. The Assessment Bill expressly allows for such retrospective application to ensure that regulation amendments may operate retrospectively to comply with the OECD Agreed Administrative Guidance as they evolve over time. It is important for the Rule making power to apply retrospectively to ensure that tax that is payable in accordance with the Rules is collected and that Australia remains consistent with the GloBE Inclusive Framework, even as Agreed Administrative Guidance evolves over time to reduce ambiguities within the OECD GloBE Model Rules. Prompt application of the Rules facilitates an early and correct understanding of the law for stakeholders. [Section 32 of the Assessment Bill]

2.80 Any legislative instruments made under the Rules can also be retrospective. Given that the OECD envisage further refinements to the OECD GloBE Model Rules via the distribution of Agreed Administrative Guidance. It is imperative that legislative instruments have the option to be retrospective to be in line with the release of documents approved by the OECD Inclusive Framework. This design approach is necessary and appropriate to keep the legislation focused, easily accessible and flexible and to ensure certainty for taxpayers about the interpretation and operation of the Minimum Tax law. [Section 32 of the Assessment Bill]

2.81 The ability for the Rules and legislative instruments made under the Rules to apply retrospectively is an important feature of Australia's incorporation of the GloBE Rules, as qualified status can only be achieved if the Rules are implemented in a manner consistent with the GloBE Rules and ongoing release of further OECD Agreed Administrative Guidance. The retrospective application will not be to the detriment of individuals, as the retrospective application does not allow for the making of regulations that apply retrospectively to make a person liable to an offence or civil penalty, and the Rules apply in the main to MNE Groups. The retrospective application also does not allow for the imposition of a new tax or to directly amend the text of the Assessment Bill. Retrospective application of the Rules is limited to the extent it complies with the Agreed Administrative Guidance. This provides a safeguard that retrospectivity will only occur to maintain qualified status at the OECD level.

Location of an Entity

2.82 Each Constituent Entity is treated as being located in a particular jurisdiction. The principle underlying the provisions that determine the location of an Entity is to follow the treatment under local law. However, certain Constituent Entities may not be liable for tax anywhere and may be treated as "Stateless Entities". The provisions apply for opaque Entities, Flow-through Entities and Permanent Establishments. Where an Entity changes its location during the Fiscal Year, it is taken to be located in the jurisdiction in which it was located at the start of that Fiscal Year. [Sections 40 to 42 and 44 of the Assessment Bill]

2.83 Following this principle, an Entity that is not a Flow-through Entity will be treated as being located in Australia if it is an 'Australian entity' within the meaning of the ITAA 1997. This definition takes the meaning of that term as provided in section 336 of the ITAA 1936, which covers an entity that is a Part X Australian resident. The effect of this is that an Entity that is not a Flow-through Entity is an Australian entity and is therefore located in Australia if it is an Australian resident within the meaning of section 6 of the ITAA 1936 and it is not deemed to be a resident of a foreign jurisdiction by any applicable tie-breaker rules in an Australian tax treaty. [Subsection 40(1) and paragraph 40(2)(a) of the Assessment Bill]

2.84 If an Entity that is not a Flow-through Entity is resident in a jurisdiction outside of Australia based on its place of management, place of creation, or similar criterion, it will be treated as being located in that jurisdiction. [Subsection 40(1) and paragraph 40(2)(b) of the Assessment Bill]

2.85 If such Entity, falls into neither of these above categories, it is located in the jurisdiction where it is created. [Subsection 40(1) and paragraph 40(2)(c) of the Assessment Bill]

Location of a Flow-through Entity

2.86 An Entity that is a Flow-through Entity is located in the jurisdiction where it was created if the Entity is either a UPE, or it is required to apply a Qualified IIR. This allows jurisdictions to impose a Qualified IIR on Flow-through Entities that are created in that jurisdiction. [Section 41 of the Assessment Bill]

2.87 Where a Flow-through Entity is not a UPE and is not required to apply a Qualified IIR in a particular jurisdiction, it is a Stateless Constituent Entity of the MNE Group. [Subsections 41(2) and (3) of the Assessment Bill]

Location of a Permanent Establishment

2.88 The location of a Permanent Establishment is determined with reference to the definition of Permanent Establishment under the Assessment Bill, which broadly covers a Permanent Establishment under any applicable tax treaty or the OECD Model Tax Convention, or the jurisdiction that taxes the income from the carrying on of business in that jurisdiction. If any of these situations apply, as set out in paragraphs (a), (b) or (c) of the definition of Permanent Establishment, the Permanent Establishment is located in the jurisdiction mentioned in that paragraph. These provisions ensure that the location of a Permanent Establishment can be determined even where different jurisdictions may treat places of business differently. [Paragraphs 19(1)(a), (b) and (c) and subsections 42(1) and (2) of the Assessment Bill]

2.89 Paragraph (d) applies where the residence jurisdiction exempts the income from a resident's operations (or a portion of its operations) on the grounds that they are conducted outside of the residence jurisdiction. In this case, the Permanent Establishment will be treated as a Stateless Constituent Entity. [Paragraph 19(2)(d) and subsection 42(3) of the Assessment Bill]

Dual-located entities

2.90 For the purposes of the ETR and top-up tax computation, the tax attributes of a Constituent Entity can only be considered in one jurisdiction. Additionally, to avoid double taxation, a Constituent Entity can only be required to apply an IIR or UTPR top-up tax in one jurisdiction.

2.91 To address situations where a Constituent Entity, other than a Permanent Establishment, is located in two or more jurisdictions, a Constituent Entity is taken to be located, for the Fiscal Year, in the jurisdiction worked out in accordance with the Rules, unless it is a Stateless Constituent Entity. [Section 43 of the Assessment Bill]

Commencement, application, and transitional provisions

2.92 The Assessment Bill commences on the day after it receives Royal Assent and applies in relation to Fiscal Years starting on or after 1 January 2024, with the exception of the provision for Australian UTPR tax under subsection 10(1) which applies in relation to Fiscal Years starting on or after 1 January 2025. [Subsections 5(1) and (2) of the Assessment Bill]

2.93 The Assessment Bill extends to every external Territory and acts, omissions, matters and things outside Australia. This ensures that the Minimum Tax law appropriately applies as part of the OECD-led, coordinated global approach to combat multinational tax avoidance. [Section 4 of the Assessment Bill]

Chapter 3: Treasury Laws Amendment (Multinational - Global and Domestic Minimum Tax) (Consequential) Bill 2024

Outline of chapter

3.1 This Chapter explains the operation of the Treasury Laws Amendment (Multinational—Global and Domestic Minimum Tax) (Consequential) Bill 2024 (Consequential Bill).

3.2 The Consequential Bill sets out the consequential and miscellaneous provisions necessary for the collection and recovery of Australian IIR/UTPR tax and Australian DMT tax. Both Australian IIR/UTPR tax and Australian DMT tax link into the existing machinery provisions in the TAA.

3.3 The Commissioner has general administration of the Assessment Bill. Giving the Commissioner general administration brings the Assessment Bill within the definition of taxation law and ensures that a liability to pay either Australian IIR/UTPR tax or Australian DMT tax is a tax- related liability.

3.4 The amendments provide for the lodgment of returns, assessments and collection for both Australian IIR/UTPR tax and Australian DMT tax. Shortfall interest charge, general interest charge and penalties can apply in respect of liabilities that arise under the Assessment Bill.

3.5 The amendments allow the Commissioner to issue rulings about the operation of the Assessment Bill, either as public rulings or as private rulings upon application and allows taxpayers to object and appeal against assessments.

3.6 The amendments provide obligations to keep records for Australian IIR/UTPR tax and Australian DMT tax.

Summary of new law

3.7 These consequential and miscellaneous amendments are necessary for the administration of Australian IIR/UTPR tax and Australian DMT tax.

3.8 To reduce the compliance burden on taxpayers, the amendments link into the existing administrative framework in the TAA with few modifications except as required to be consistent with the GloBE Rules.

Detailed explanation of new law

General Administration of the Assessment Bill

3.9 The Commissioner has general administration of the Assessment Bill. This brings the Assessment Bill within the definition of taxation law as defined in subsection 995-1(1) of the ITAA 1997 and consequently enlivens a number of provisions within the existing administrative framework used by the Commissioner in the administration of these taxation laws. [Schedule 1, item 57, subdivision 356-D in Schedule 1 to the TAA]

3.10 As the Assessment Bill is a taxation law, several existing provisions of the TAA apply in relation to the Assessment Bill, including provisions relating to information gathering and penalties.

3.11 The Commissioner's powers to obtain information and evidence in relation to a taxation law in Subdivision 353-A in Schedule 1 to the TAA apply in relation to the Assessment Bill. This includes the Commissioner's ability to exercise the powers in sections 353-10 and 353-15 to gather information for purposes connected with the Assessment Bill.

3.12 Information gathered for purposes related to the Assessment Bill is protected information as defined in section 355-30 in Schedule 1 to the TAA. This ensures this information is covered by the secrecy provisions in Division 355 in Schedule 1 to the TAA.

3.13 Administrative penalty provisions in Schedule 1 to the TAA which refer to a taxation law will apply in relation to the Assessment Bill. These include penalties for making a false and misleading statement under Subdivision 284-B and penalties for failing to lodge under Division 286.

3.14 Where an administrative penalty is imposed under Part 4-25 in Schedule 1 to the TAA in relation to the Assessment Bill, as part of the process of assessing the amount of the penalty, the Commissioner is required to determine if remission is appropriate under section 298-20 in Schedule 1 to the TAA. Where a penalty is imposed, the taxpayer has objection rights in certain circumstances, consistent with subsection 298-20(3) in Schedule 1 to the TAA.

3.15 Offences which refer to a taxation law also apply in relation to the Assessment Bill.

3.16 A liability raised under the Assessment Bill is a tax-related liability as defined in section 255-1 in Schedule 1 to the TAA. This ensures that:

- •

- the Commissioner can recover debts arising from the non-payment of these liabilities;

- •

- the Commissioner can issue an offshore information notice under section 353-25 in Schedule 1 to the TAA to collect information relevant to the assessment of Australian IIR/UTPR tax and Australian DMT tax;

- •

- the penalties for failing to lodge a document necessary to determine a tax-related liability under subsection 284-75(3) in Schedule 1 to the TAA may apply; and

- •

- the Commissioner may allocate an entity's liability for Australian IIR/UTPR tax and Australian DMT tax to the entity's running balance account under Part IIB of the TAA so that any available credit may offset these top-up tax liabilities.

3.17 The amendments include new Division 127 in Schedule 1 to the TAA providing rules for tax returns and tax assessments, and new Division 128 in Schedule 1 to the TAA providing rules imposing onto other entities the obligations and liabilities of various entities under the Minimum Tax law.

3.18 For top-up tax purposes, the Minimum Tax law recognises Permanent Establishments as Constituent Entities. For lodgment and payment obligations, those liabilities and obligations are placed on the Main Entity because the Permanent Establishment has no legal capacity. A Main Entity is a Group Entity. For this reason, Division 127 in Schedule 1 to the TAA refers to Group Entity. While the Minimum Tax law treats Permanent Establishments as Constituent Entities, this fiction is not carried through to the administrative provisions in the TAA. Ensuring these liabilities and obligations are always imposed on the Main Entity in respect of a Permanent Establishment ensures consistent treatment of such entities within the TAA.

3.19 The amendments insert new terms in the Dictionary definitions in Division 995 of the ITAA 1997. Many of these include terms beginning with "GloBE" to distinguish the term from a similar term in the tax law, for example GloBE Entity is a new term that is different from entity in the ITAA 1997. [Schedule 1, items 27, 28 and 29, subsection 995-1(1) of the ITAA 1997]

Returns

3.20 The Consequential Bill inserts Subdivision 127-A in Schedule 1 to the TAA to require the following returns to be given to the Commissioner:

- •

- A GloBE Information Return – an obligation to lodge this standardised return with the Commissioner is consistent with the GloBE Rules.

- •

- An Australian IIR/UTPR Tax Return – this return supplements the GloBE Information Return and contains information for the purposes of administering, assessing and collecting Australian IIR/UTPR tax.

- •

- An Australian DMT Tax Return – this return supplements the GloBE Information Return and contains information for the purposes of administering, assessing and collecting Australian DMT tax. [Schedule 1, item 35, Division 127, sections 127-1 to 127-65 in Schedule 1 to the TAA]

3.21 The obligation to prepare a GloBE Information Return is separate from the requirement to declare information and pay taxes for the purposes of assessment under a tax return. That is, a GloBE Information Return is not a tax return giving rise to an assessment. The Australian IIR/UTPR Tax Return and Australian DMT Tax Return form the basis of the Commissioner's assessment of Australian IIR/UTPR tax and Australian DMT tax, respectively. [Schedule 1, item 35, subsections 127-5(1), 127-35(1) and (2) and 127-45(1) and (2) in Schedule 1 to the TAA]

3.22 A GloBE Information Return, Australian IIR/UTPR Tax Return and Australian DMT Tax Return must be lodged electronically and be in the approved form. As the Assessment Bill is a 'taxation law', an administrative penalty under section 286-75 in Schedule 1 to the TAA applies for each return not lodged. [Schedule 1, item 35, subsections 127-5(2), 127-35(3) and 127-45(3) in Schedule 1 to the TAA]

3.23 The due date for lodgment of the returns is harmonised. The Australian IIR/UTPR Tax Return and the Australian DMT Tax Return must be lodged within the time that is specified for the lodgment of the GloBE Information Return. This is consistent with the GloBE Rules, which stipulate lodgment to be within 15 months after the end of every Fiscal Year. However, an exception applies for the first Fiscal Year in which a jurisdiction's domestic law implementation of the GloBE Rules is applied by an MNE Group, where the return must be given within 18 months after the end of the Fiscal Year. [Schedule 1, item 35, subsections 127-60(1) and (2) in Schedule 1 to the TAA]

3.24 A transitional provision for short Reporting Fiscal Years is explained from paragraph 3.139.

3.25 The Commissioner does not have discretion to defer time for lodgment of the GloBE Information Return or for providing notification that a GloBE information Return has been provided to a foreign government agency. This is consistent with the due date for filing under the GloBE Rules. The Commissioner may defer the time for lodgment of the Australian IIR/UTPR Tax Return and Australian DMT Tax Return. [Schedule 1, item 35, subsection 127-60(3) in Schedule 1 to the TAA]

3.26 If a Constituent Entity is a Permanent Establishment, the Main Entity in relation to that Permanent Establishment is required to give to the Commissioner a GloBE Information Return, an Australian IIR/UTPR Tax Return and an Australian DMT Tax Return in respect of that Permanent Establishment. [Schedule 1, item 35, section 127-65 in Schedule 1 to the TAA]

3.27 Where a GloBE Information Return is given to a foreign government agency, the obligation on a Group Entity located in Australia to provide the Commissioner with a GloBE Information Return is discharged when the UPE or a Designated Filing Entity files the GloBE Information Return with the tax administration of the foreign jurisdiction where it is located. That foreign jurisdiction must have a Qualifying Competent Authority Agreement with Australia. [Schedule 1, items 27 and 35, the definition of Designated Filing Entity in subsection 995-1(1) of the ITAA 1997, sections 127-20 and 127-25 in Schedule 1 to the TAA]

3.28 A Qualifying Competent Authority Agreement is an agreement between two competent authorities regarding the automatic exchange of GloBE Information Returns. At least one of the authorities must be a Competent Authority of Australia. [Schedule 1, items 29 and 35, the definition of Qualifying Competent Authority Agreement in subsection 995-1(1) of the ITAA 1997 and subsection 127-20(3) in Schedule 1 to the TAA]

3.29 In this way, the return filing obligations operate so that the UPE or a Designated Filing Entity of the MNE Group can file a single GloBE Information Return covering all Constituent Entities in the MNE Group, which can be provided to all tax administrations with at least one Constituent Entity located in their jurisdiction through appropriate information exchange mechanisms.

3.30 If a GloBE Information Return is given to a foreign government agency, the Commissioner must be notified within the time specified. The notification must be in the approved form and lodged electronically. It must state the identity and jurisdiction of the UPE or Designated Filing Entity that filed the GloBE Information Return. Each Group Entity of the MNE Group located in Australia is required to give such notice. However, where a Designated Local Entity gives the notice all other Group Entities that are located in Australia for that Fiscal year are taken to have given such notice. [Schedule 1, item 35, subsections 127-30(1), (2) and (3) in Schedule 1 to the TAA]

GloBE Information Return

3.31 The GloBE Information Return is a standardised form that provides each jurisdiction's tax administration with the information required to assess an entity's tax liability consistent with the GloBE Rules. It is in accordance with the standardised return developed in accordance with the GloBE Implementation Framework. Currently, that return is the standardised return published by the OECD on 17 July 2023. In this way, the GloBE Information Return is consistent for information reporting requirements across implementing jurisdictions. Where relevant, due consideration should be given to the Guidance to the GloBE Information Return, published by the OECD Inclusive Framework on 17 July 2023.

3.32 As set out in the GloBE Rules, the GloBE Information Return is intended to capture general information, corporate structure, the ETR computation, computation and allocation of top-up tax liabilities and any elections made for the relevant Fiscal Year, subject to the dissemination approach for the GloBE Information Return detailed in the standardised return published by the OECD on 17 July 2023, as amended from time to time. The dissemination approach refers to the approach agreed upon by the OECD Inclusive Framework for categorising information available to each implementing jurisdiction based on their GloBE taxing rights. These taxing rights depend on whether Constituent Entities are located in that jurisdiction and the rule order applying to the MNE Group structure. However, the dissemination approach does not preclude the GloBE Information Return from being lodged in an approved form.

Content requirements of the GloBE Information Return

3.33 Each Group Entity of an Applicable MNE Group that is located in Australia at the start of the Fiscal Year must lodge a GloBE Information Return that is in accordance with the GloBE Implementation Framework and includes the following information:

- •

- identification number of the Constituent Entity;

- •

- location of the Constituent Entity;

- •

- status of the Constituent Entity under the GloBE Rules;

- •

- information on the overall corporate structure of the group including controlling interests;

- •

- all information relevant to the determination of the following in relation to the Applicable MNE Group:

- -

- ETR for each jurisdiction

- -

- top-up tax of each Constituent Entity

- -

- top-up-tax of a member of the JV Group (under Chapter 6 of the GloBE Rules); and

- -