Taxation Ruling

TR 2022/4

Income tax: section 100A reimbursement agreements

This version is no longer current. Please follow this link to view the current version. |

-

Please note that the PDF version is the authorised version of this ruling.There is a Compendium for this document: TR 2022/4EC .This document has changed over time. View its history.

| Table of Contents | Paragraph |

|---|---|

| What this Ruling is about | |

| Ruling | |

| Connection requirement | |

| Agreement | |

| Relevant connection between entitlement and agreement | |

| Benefits to another requirement | |

| Tax reduction purpose requirement | |

| Ordinary dealing exception | |

| Family objectives | |

| Commercial objectives | |

| Consequences of section 100A - trustee liable for income tax and beneficiary relieved | |

| Deeming | |

| Division 6 and related consequences | |

| Capital gains and franked distributions | |

| Date of effect | |

| Appendix 1 - Explanation | |

| General | |

| History of enactment | |

| Current and prior case law | |

| Elements of section 100A | |

| Connection requirement (subsections 100A(1) to (6)) | |

| A present entitlement | |

| An identified agreement, arrangement or understanding | |

| An entitlement that occurs in connection with or as a result of the reimbursement agreement | |

| Benefits to another requirement (subsections 100A(7), (11) and (12)) | |

| Tax reduction purpose requirement (subsection 100A(8)) | |

| Ordinary dealing exception (subsection 100A(13)) | |

| Dealing | |

| Example 1 - identifying family objectives | |

| Ordinary family or commercial dealing - the core test | |

| Family or commercial objectives | |

| Implications of core test | |

| Commonplace transactions and intra-family transactions | |

| Factors which may point to an absence of ordinary family or commercial dealing | |

| Relevance of cultural factors | |

| Example 2 - cultural practice of gifting | |

| Example 3 - cultural practice to support older relatives | |

| Example 4 - cultural practice of not accepting entitlement | |

| Application of other tax laws | |

| Consequences - trustee liable for income tax and beneficiary relieved | |

| Division 6 and related consequences | |

| Capital gains and franked distributions | |

| Example 5 - allocation of capital gains when section 100A applies to a present entitlement | |

| Appendix 2 - Examples | |

| Example 6 - trust established under a will | |

| Example 7 - distribution to spouses with mixed finances | |

| Example 8 - gift from parents to a child | |

| Example 9 - unpaid entitlements held on trust | |

| Example 10 - non-commercial loan between family members | |

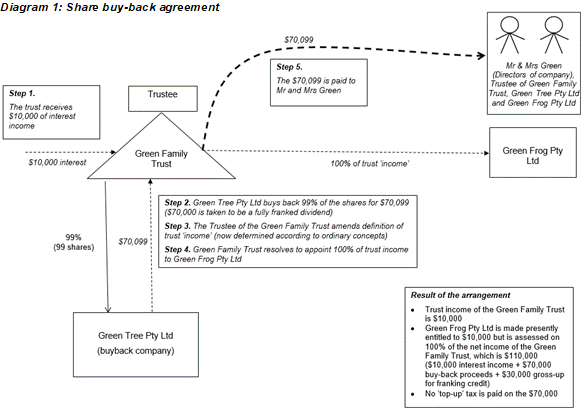

| Example 11 - share buy-back arrangement | |

| Example 12 - circular flow of funds | |

| Appendix 3 - Alternative views | |

| Scope of section 100A beyond trust stripping | |

| 'Counterfactual' required to satisfy tax reduction purpose in subsection 100A(8) | |

| Tax avoidance not relevant to ordinary dealing exception | |

| Section 100A only unwinds the label of 'present entitlement' |

Relying on this Ruling

Relying on this Ruling

This publication (excluding appendixes) is a public ruling for the purposes of the Taxation Administration Act 1953. If this Ruling applies to you, and you correctly rely on it, we will apply the law to you in the way set out in this Ruling. That is, you will not pay any more tax or penalties or interest in respect of the matters covered by this Ruling. |

1. It is common for trust beneficiaries to be made presently entitled to trust income.

2. Sometimes (though much less commonly), a beneficiary's present entitlement to a share of trust income arises out of, or in connection with, an arrangement:

- •

- involving a benefit being provided to another person

- •

- intended to have the result of reducing someone's tax liability, and

- •

- entered into outside the course of ordinary family or commercial dealing.

3. In these cases, section 100A of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1936 (ITAA 1936) generally applies to make the trustee, rather than the presently entitled beneficiary, liable to tax at the top marginal rate.

4. All legislative references in this Ruling are to the ITAA 1936, unless otherwise indicated.

5. This Ruling provides the Commissioner's view about these arrangements and the 4 basic requirements for section 100A to apply, namely that:

- •

- The following 3 requirements are satisfied

- -

- 'Connection requirement' - broadly stated, the present entitlement (or amount paid or applied for the benefit of the beneficiary) must have arisen out of, as a result of or in connection with a reimbursement agreement (being an agreement, understanding or arrangement that has the 3 qualities described in the following points in this paragraph).

- -

- 'Benefit to another requirement' - the agreement must provide for the payment of money or transfer of property to, or provision of services or other benefits for, a person other than that beneficiary.

- -

- 'Tax reduction purpose requirement' - a purpose of one or more of the parties to the agreement must be that a person would be liable to pay less income tax for a year of income.

- •

- The 'ordinary dealing exception' is not satisfied - the agreement must not be one that has been 'entered into in the course of ordinary family or commercial dealing'.

6. For the purposes of this Ruling and for ease of expression:

- •

- 'beneficiary' excludes a beneficiary under a legal disability, other than a beneficiary in the capacity of a trustee of another trust estate

- •

- 'present entitlement' refers to a beneficiary's 'present entitlement to a share of income of the trust estate', and

- •

- 'income paid or applied' to or for a beneficiary refers to 'income of the trust estate paid to, or applied for the benefit of, the beneficiary'.

Ruling

7. Section 100A will apply to so much of the share of trust income that a beneficiary is presently entitled to, and/or that has been paid to them, or that has been applied for their benefit (that share) as:

- •

- satisfies the

- -

- connection requirement

- -

- benefit to another requirement

- -

- tax reduction purpose requirement, and

- •

- does not satisfy the ordinary dealing exception

as those requirements are described in this Ruling.

8. To satisfy the connection requirement, there needs to be a relevant connection between:

- •

- all or part of a beneficiary's present entitlement, or all or part of the income paid to or applied for the beneficiary, and

- •

- an agreement (that meets the requirements to be a reimbursement agreement).

9. There will be such a relevant connection to the extent that:

- •

- either

- -

- the beneficiary is (in fact) presently entitled to a share of trust income and all or part of their present entitlement to that share arose

- o

- out of a reimbursement agreement, or

- o

- by reason of any act, transaction or circumstance that occurred in connection with or as a result of a reimbursement agreement[1]

- or

- -

- the beneficiary is deemed to be presently entitled to that share and all or part of that share was paid to them or applied for their benefit as a result of

- o

- a reimbursement agreement, or

- o

- any act, transaction or circumstance that occurred in connection with or as a result of a reimbursement agreement[2],

- and

- •

- where the beneficiary is a beneficiary in their capacity as a trustee of another trust (interposed trust), the non-flow through requirement is also satisfied: That is, no beneficiary of the interposed trust is or was presently entitled[3] to so much of the income of the interposed trust that is attributable to the trustee beneficiary's share (or part share, as the case may be).[4]

10. An 'agreement' is defined widely for section 100A purposes to include arrangements and understandings.[5] Those terms have their ordinary and legal meaning in the context in which they appear. An agreement can be formal or informal, express or implied, and need not be enforceable or intended to be enforceable. An agreement may be inferred from the surrounding circumstances or the conduct of the parties.

11. While an agreement requires 2 or more parties, an exact understanding of the nature and extent of the agreement (or of the benefits to be provided under it) is not required between all of its parties.

12. An agreement can cover a range of things, including a series of steps[6] or concerted action towards a purpose.[7]

Relevant connection between entitlement and agreement

13. For section 100A to apply, as described in paragraphs 7 to 9 of this Ruling, a relevant connection is required between all or part of the beneficiary's present entitlement (or the income paid to or applied for them) and the relevant reimbursement agreement. This need not be a direct causal connection. It is sufficient that all or part of the present entitlement has arisen from (or relevant payment or application has resulted from) another act, transaction or circumstance that occurred in 'connection with' or 'as a result of' the reimbursement agreement.

14. Without limiting the scope of the connection sufficient for section 100A to apply, where the amount of trust income a beneficiary is made presently entitled to (or is paid or has applied for their benefit) exceeds the amount that they would have been (or could reasonably be expected to have been) made so entitled to (or so paid or applied for their benefit) absent either the reimbursement agreement or relevant act, transaction or circumstance occurring in connection with the reimbursement agreement, that excess is taken to have arisen out of (or have been paid or applied as a result of) the reimbursement agreement.[8]

15. The amount the taxpayer would have been made entitled to (or have been paid or had applied for their benefit) absent the reimbursement agreement (or absent the relevant act, transaction or circumstance occurring in connection with the reimbursement agreement) involves a prediction as to events which would have otherwise taken place. The prediction must be sufficiently reliable for it to be regarded as reasonable.

16. For a present entitlement to income or an amount of income that is paid or applied for the benefit of a beneficiary to arise from or in connection with or as a result of a reimbursement agreement, that agreement must have occurred simultaneously with or have been in existence prior to the time the entitlement arose or when the payment or application occurred, as the case may be. However:

- •

- conduct of the parties before and after that time may be relevant to establishing the existence of an agreement by that time (for example, where behaviour is repeated), and

- •

- neither the presently entitled beneficiary nor the trustee needs to necessarily be a party to the agreement or even be in existence when the agreement is made.[9]

Benefits to another requirement

17. For an agreement to be a reimbursement agreement, it must provide for the payment of money (including via loans or the release, abandonment, failure to demand payment of or the postponing of the payment of a debt), transfer of property to or provision of services or other benefits for one or more persons other than the beneficiary alone.[10]

18. An agreement that (or which includes that) a beneficiary will not demand payment of an amount to which they are presently entitled would be one that provides for the provision of benefits for a person other than the beneficiary alone.

19. Despite the label given to 'reimbursement agreements', the payment of money to, transfer of property to or provision of services or other benefits for a person other than the beneficiary alone need not necessarily be a 'reimbursement' as such to meet the requirements of subsection 100A(7). In particular, there is no requirement that the relevant money, property, services or other benefits provided to a person other than the beneficiary alone be sourced from, equal to or otherwise be referrable to the share of trust income the beneficiary is presently entitled to receive, was paid or that was applied on their behalf.[11]

Tax reduction purpose requirement

20. For an agreement to be a reimbursement agreement, one or more of the parties to the agreement must have entered into it for a purpose (which need not be a sole, dominant or continuing purpose) of securing that a person would be liable to pay less tax in an income year than they otherwise would have been liable to pay in respect of that income year (a tax reduction purpose).[12]

21. The reference to purpose is to an actual purpose of entering into the agreement, which may be determined by reference to the parties' own evidence as to their purposes for entering into the agreement and to the objective facts and circumstances including the financial, taxation and other consequences of the transaction entered into.[13]

22. For there to be a tax reduction purpose, it is not necessary that an alternative postulate be established so as to identify a specific amount of tax that would be avoided by an identified person.[14]

23. For the tax reduction purpose requirement to be satisfied:

- •

- the person whose tax liability is to be reduced or eliminated need not necessarily be a party to the reimbursement agreement[15]

- •

- an intended reduction in a person's tax liability need not actually be achieved[16]

- •

- the intended income tax liability reduction can be in relation to any year of income, meaning that a purpose of deferring tax to a later year would be sufficient to demonstrate the tax reduction purpose.

24. The purpose of an adviser can be relevant to determining whether a tax reduction purpose exists. An agreement can extend to an agreement or understanding to carry out a series of steps.[17] Where the adviser is a party to the agreement, the purpose of the adviser will be directly relevant. Further, the purpose of the adviser may be imputed to a party to the relevant agreement who acts in accordance with the adviser's advice.[18]

25. Agreements entered into in the course of ordinary family or commercial dealing are not reimbursement agreements.[19] This 'ordinary dealing' test is an objective test applied, at least principally, from the perspective of the persons whose purposes are relevant to the operation of section 100A.[20]

26. It is the whole dealing 'in the course of' which the agreement is entered into (including the transaction, set of transactions or other actions) which must have the quality of 'ordinary family or commercial dealing'. It is not sufficient that each step in a series of connected transactions is capable of being described as 'ordinary'.[21]

27. To test whether there is ordinary family or commercial dealing, consider all relevant circumstances, including what is sought to be achieved by the dealing (in particular, whether it is explained by the family or commercial objectives it will achieve) and whether the steps that comprise the dealing will likely achieve those objectives. It can also be relevant to consider the historical behaviour of the parties[22] and whether the dealing:

- •

- is artificial or contrived

- •

- is overly complex

- •

- contains steps that are not needed to achieve the family or commercial objectives, or

- •

- contains steps that might be explained instead by objectives different to those said to be behind the ordinary family or commercial dealing.[23]

28. If the objective of a dealing can properly be explained as the payment of less tax to maximise group wealth, rather than some other objective which is a family or commercial objective, it is not an ordinary family or commercial dealing.

29. 'Family' in 'ordinary family or commercial dealing' takes its ordinary meaning. It refers to a relationship of natural persons based on birth or affinity, and may often involve co-residence. Family is not limited to any particular type of family relationship that is more common at a point in time than others.

30. The ordinary dealing exception does not apply simply because all parties to an agreement are family members. To be entered into in the course of ordinary dealing, the transactions between family members and their entities must be able to be explained as achieving family or commercial objectives.

31. A usual characteristic of dealings to achieve commercial objectives is that the parties to those dealings advance their own commercial interests.

32. The absence of arm's length dealings or market value does not, of itself, prevent a dealing from being explained as achieving the commercial objectives of the parties to the transactions.

Consequences of section 100A - trustee liable for income tax and beneficiary relieved

33. Where it applies, the deeming in section 100A creates a fictitious set of facts which are substituted for reality. The deeming is stated to apply for the purposes of the ITAA 1936.

34. Specifically, to the extent that the share of income of a trust estate that a beneficiary is presently entitled to (or that has been paid to them or applied for their benefit) meets the connection, benefits to another and tax reduction purpose requirements, and the ordinary dealing exception does not apply, section 100A will apply as follows:

- •

- Where those requirements are met for all or part of an actual present entitlement, the beneficiary shall be deemed not to be, and never to have been, presently entitled to the relevant trust income. The fictitious set of facts created by the deeming in section 100A in these cases is that the beneficiary does not have the rights or entitlements that would cause them to be presently entitled to the relevant income of the trust estate.[24]

- •

- Where those requirements are met for a case where the beneficiary was in fact paid that share or it was in fact applied for their benefit, the relevant trust income will be deemed not to have been paid or to have been applied for the beneficiary.

35. The deeming takes effect for those purposes of the ITAA 1936 that operate to provide taxation consequences in relation to the entitlement that is the subject of section 100A. However, the substitution of the fictitious set of facts does not extend to treat an entitlement as having arisen for another person (such as a default beneficiary).[25]

Division 6 and related consequences

36. Any assessment of the net income of the trust estate to a beneficiary that would otherwise arise under section 97 will be proportionately reduced by the share of the income of the trust estate. Section 100A deems the beneficiary not to be presently entitled to or to have received or had applied that amount for their benefit. Any proportionate assessment of the net income of the trust estate to the trustee that would otherwise have arisen under section 98[26] in respect of such a share would be likewise reduced, with section 98A[27] then having no application in respect of that share.

37. The trustee is assessed and liable to pay tax on the relevant share of the net income of the trust under section 99A relating to so much of the income of the trust estate covered by the section 100A deeming, as section 100A has created the statutory fiction that no beneficiary is presently entitled to this part.

38. The deeming operates for purposes outside of Division 6, which are relevant to the taxation consequences of the trust entitlement:

- •

- No franking credits will arise for a corporate beneficiary in respect of tax otherwise payable in relation to an entitlement which has been switched off by the operation of section 100A.

- •

- No withholding tax liability will arise in respect of entitlements which would be subject to subsection 128A(3) in respect of a non-resident beneficiary, where the present entitlement is switched off by the operation of section 100A.

- •

- In the case of a corporate beneficiary, because the entitlement is taken not to arise, there will be taken to be no entitlement which could be the subject of a loan to the trustee under section 109D. Division 7A in those circumstances would not operate in respect of the entitlement.

However, for other purposes of the ITAA 1936 which are not about the taxation of trust net income flowing from the entitlement which was the subject of section 100A, the deeming does not operate to reduce or disregard the assets of the beneficiary.

Capital gains and franked distributions

39. The deeming also has effect for the assessment of trust capital gains and franked distributions.

40. For 2010-11 and following income years, the tax treatment of capital gains and franked distributions that are included in the net income of a trust estate is determined by the application of specific rules in Subdivisions 115-C and 207-B of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (ITAA 1997)[28] (the streaming rules). This tax treatment is one of the 'purposes of the Act' for which the fictional state of affairs deemed by section 100A would apply.

41. Where a beneficiary would otherwise be 'specifically entitled'[29] to a capital gain or franked distribution (or part thereof) included in the income of the trust estate (a gain or distribution) on the basis that they have received or have an entitlement (by reason of their present entitlement) to receive (and therefore expect to receive) the financial benefits in respect of that gain or distribution, the operation of section 100A (in creating a statutory fiction where that receipt or entitlement did not arise) will result in no beneficiary being specifically entitled to that gain or distribution. It will therefore also result in the allocation of the amount of the gain or distribution between the beneficiaries and trustees according to their respective adjusted Division 6 percentages[30], worked out in that fictional state of affairs.

42. Where no one is specifically entitled[31], the operation of section 100A in creating a statutory fiction will result in an adjustment of the parties' adjusted Division 6 percentages for the purposes of the streaming rules.

43. This Ruling applies to arrangements both before and after its issue. However, the Ruling will not apply to you to the extent that it conflicts with the terms of settlement of a dispute agreed to before the date of issue of the Ruling (see paragraphs 75 to 76 of Taxation Ruling TR 2006/10 Public Rulings).

Note: The Commissioner has published Practical Compliance Guideline PCG 2022/2 Section 100A reimbursement agreements - ATO compliance approach, which sets out the risk assessment framework and our compliance approach to a range of trust arrangements to which section 100A may apply, including arrangements entered into in current and prior income years.

Commissioner of Taxation

8 December 2022

Appendix 1 - Explanation

This Explanation is provided as information to help you understand how the Commissioner's preliminary view has been reached. It does not form part of the proposed binding public ruling.

This Explanation is provided as information to help you understand how the Commissioner's preliminary view has been reached. It does not form part of the proposed binding public ruling.

|

44. Section 100A is an anti-avoidance provision that was enacted in 1979. Broadly, and subject to the exception for an agreement entered into in the course of ordinary family or commercial dealing, section 100A applies in cases in which a beneficiary has become presently entitled to trust income where it has been agreed that another person will benefit, and that agreement is made by any of its parties with a purpose that some person will pay less or no income tax as a result.

45. Unlike the general anti-avoidance provisions in Part IVA, section 100A does not require the making of a determination by the Commissioner[32]; it is a self-executing provision which operates according to its terms.

46. According to the Explanatory Memorandum[33], section 100A:

... look[s] to the existence of an agreement or arrangement that is entered into otherwise than in the course of ordinary family or commercial dealing and under which present entitlement to a share of trust income is conferred on a beneficiary in return for the payment of money or the provision of benefits to some other person, company or trust.

...

Sub-section (8) will effectively exclude from the scope of section 100A any agreement that was not entered into or carried out for a purpose of securing for any person a reduction in that person's liability to income tax in respect of a year of income, i.e., section 100A is only concerned with tax avoidance arrangements.

47. At the date of publication of this Ruling, there are 2 Federal Court decisions which concern section 100A that are subject to appeal in the Full Federal Court. Those decisions are Guardian and BBlood.

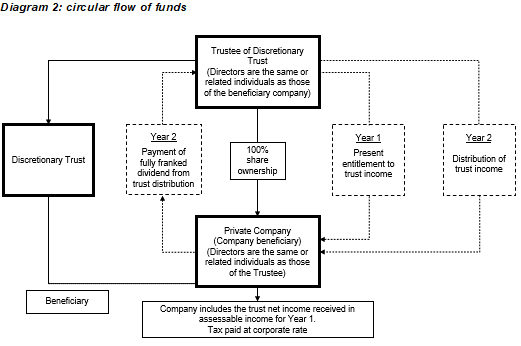

48. In Guardian, trust income was distributed to a corporate beneficiary, returned as a franked dividend to the trustee (the sole shareholder) in the following year and then distributed to a non-resident individual. The effect of the transactions was to convert the original trust income into franked dividend income, which had the result of capping the tax on the income at the corporate rate, compared to the higher rates that would have applied if the original trust income had been distributed to that individual directly. The Commissioner contended the transactions occurred as a series of steps under an agreement which was a 'reimbursement agreement' to which section 100A would apply.[34]

49. The Court (Logan J) allowed the taxpayer's appeals. His Honour concluded that on the evidence, including the testimony of witnesses, the agreement contended by the Commissioner did not exist at the time when the present entitlement of the corporate beneficiary arose. That is, the connection requirement was not satisfied in respect of the agreement contended by the Commissioner.

50. His Honour did, however, find that a narrower agreement that did not include the payment of a dividend by the corporate beneficiary to the trustee or the following steps existed at the relevant time.[35] This narrower agreement was not a reimbursement agreement as it was entered into in the course of ordinary family or commercial dealing such that the ordinary dealing exception applied.[36] His Honour made further observations that there could otherwise be no reimbursement agreement because the benefit to another requirement was not satisfied (it provided only for the payment of money to a beneficiary).[37] His Honour made further comments on the operation of the ordinary dealing exception[38] and the tax reduction purpose requirement[39].

51. In BBlood, the trustee of a trust received proceeds in excess of $10 million from a buy-back of shares in a company it controlled. As a consequence of amendments to the trust deed made shortly before the buy back was conducted, these proceeds were excluded from the definition of trust income. The trustee resolved to make a newly formed corporate beneficiary presently entitled to trust income, being approximately $300,000 received from related entities. The effect of the arrangement, apart from the operation of section 100A and other integrity rules, was that the corporate beneficiary was liable to tax on the taxable receipts of the trust including the buy-back dividend of $10 million. As the share buy-back dividend was fully franked, the corporate beneficiary paid no further tax on it. The buy-back proceeds, to which the corporate beneficiary was not entitled, were retained as corpus of the trust and used for group purposes.

52. The Commissioner issued an assessment to the trustee of the trust, asserting that the series of steps constituted a reimbursement agreement. The applicant's relevant appeal was dismissed by the court (Thawley J). His Honour concluded that:

- •

- The connection requirement was satisfied: The Court held that the present entitlement both 'arose out of a reimbursement agreement' and 'arose by reason of any act, transaction or circumstance that occurred in connection with, or as a result of, a reimbursement agreement'.[40]

- •

- The benefit to another requirement was satisfied: There was no requirement that the payment referred to in subsection 100A(7) be, in substance, a reimbursement for the beneficiary being made presently entitled to the income of the trust.[41] The benefit to another requirement was satisfied even if the corporate beneficiary enjoyed the full benefit of its trust entitlement.[42]

- •

- The tax reduction purpose requirement was satisfied: The taxpayers had not discharged the onus of establishing there was not a tax reduction purpose in subsection 100A(8).[43] It is not a requirement of subsection 100A(8) to identify a definite 'alternative postulate' under which an identified amount of tax was avoided.[44]

- •

- The ordinary dealing exception did not apply: The agreement was not entered into in the course of ordinary family or commercial dealing.[45] The Court observed that the agreement was 'unusual' and '[i]ts complexity was not shown to be necessary to achieving a specific outcome sought to be achieved by a dealing aptly described as "an ordinary family or commercial dealing"'.[46]

53. The decisions in Guardian and BBlood are current sources of law that the Commissioner has taken into account in making this Ruling, with issues of contention identified throughout.

54. There has been prior judicial consideration of section 100A. The application of section 100A has been confirmed for certain arrangements where:

- (a)

- it was alleged that a trustee made more than 100 beneficiaries (non-resident relatives of the controller of the trust) presently entitled to shares of net income of the trust and subsequently obtained the authorisations of those beneficiaries that they would not call for their entitlements[47]

- (b)

- an entity with substantial carry forward losses was added (or said to be added) as a beneficiary of a trust and distributions (or purported distributions) to that entity were remitted on a substantially deferred or substantially discounted basis[48], and

- (c)

- an entity with substantial carry-forward losses was added as a beneficiary of the trust and distributions made to that entity were used to pay interest to an offshore company controlled by the same interests as controlled by the trustee of the trust.[49]

55. As set out in paragraph 5 of this Ruling, there are 4 basic requirements for the operation of section 100A:

- •

- the connection requirement (see paragraphs 57 to 76 of this Ruling)

- •

- the benefits to another requirement (see paragraphs 77 to 82 of this Ruling)

- •

- the tax reduction purpose requirement (see paragraphs 83 to 89 of this Ruling), and

- •

- the ordinary dealing exception (see paragraphs 90 to 113 of this Ruling).

56. The consequences of section 100A applying are that the trustee (and not the beneficiary) will be liable for income tax on amounts that would generally otherwise be included in the assessable income of the beneficiary in respect of the beneficiary's present entitlement (or the amount of income paid or applied for their benefit) (see paragraphs 121 to 122 of this Ruling).

Connection requirement (subsections 100A(1) to (6))

57. Subsection 100A(1) provides that where:

(a) ... a beneficiary of a trust estate who is not under a legal disability is presently entitled to a share of the income of the trust estate; and

(b)... that share or ... a part of that share ... arose out of a reimbursement agreement or arose by reason of any act, transaction or circumstance that occurred in connection with, or as a result of, a reimbursement agreement;

the beneficiary shall, for the purposes of this Act, be deemed not to be, and never to have been, presently entitled to the relevant trust income.

58. Subsection 100A(2) applies, with similar effect, for cases where a beneficiary is deemed to be presently entitled to income of the trust estate because it was paid to them or applied for their benefit.[50]

59. It follows, from the text of subsections 100A(1) and (2), that for the application of the section there must be an actual or deemed present entitlement for a beneficiary and the existence of that present entitlement, or the payment or application to or for the beneficiary (whether in full or in part), must have the required connection with an identified agreement, arrangement or understanding that is a 'reimbursement agreement'.

60. The extent to which subsections 100A(1) and (2) can apply may be modified where the beneficiary (trustee beneficiary) is presently entitled as trustee of another trust estate (the interposed trust estate).[51]

61. The non-flow through requirement in subsection 100A(3A) provides that subsection 100A(1) does not apply to so much of the trust income to which a trustee beneficiary is presently entitled (relevant trust income) that, broadly, the trustee beneficiary in turn passes on to beneficiaries of the interposed trust. Specifically, it will not apply to the extent that one or more beneficiaries of that interposed trust estate are or were presently entitled[52] to income of the interposed trust that is attributable to the relevant trust income. However, depending on the circumstances, it is possible for section 100A to apply to the present entitlement of the beneficiary of the interposed trust.

62. Subsection 100A(3B) applies similarly to exclude from the operation of subsection 100A(2) income of a trust estate that is paid to, or applied for the benefit of, a trustee beneficiary to the extent that one or more beneficiaries of the interposed trust estate are or were presently entitled[53] to income attributable to the amounts paid or applied for the benefit of the trustee beneficiary. Similarly, it is possible for section 100A to apply to the present entitlement of the beneficiary of the interposed trust.

63. Arrangements to which section 100A apply involve a person being presently entitled to or having been paid the income of a trust estate, or having had the income of a trust estate applied for their benefit (and so are deemed to be presently entitled), in connection with a reimbursement agreement.[54]

64. Section 100A is applied to the facts. Where actions taken to purportedly create a present entitlement are a sham (not intended to have their stated legal consequences), the purported appointment of income to that beneficiary is not legally effective.[55] Consequently, section 100A cannot apply in relation to that purported entitlement.[56]

65. The same result applies where a purported appointment of income is not effective for reasons other than sham. For example, if a trustee purports to appoint income to a party that is not a beneficiary of the trust.[57]

An identified agreement, arrangement or understanding

66. Subsection 100A(13) provides that in section 100A:

agreement means any agreement, arrangement or understanding, whether formal or informal, whether express or implied and whether or not enforceable, or intended to be enforceable, by legal proceedings, but does not include an agreement, arrangement or understanding entered into in the course of ordinary family or commercial dealing.

67. The meaning of the term 'agreement' is informed by the surrounding text, the context in which it appears and case law in which the phrase in subsection 100A(13) has been interpreted. Drawing on these sources, the term 'agreement':

- •

- expressly extends to 'arrangements' and 'understandings', which can be informal, express or implied, and need not be enforceable or even intended to be enforceable

- •

- has been described by the Full Federal Court as having its widest meaning[58], and

- •

- is defined to include any 'agreement, arrangement or understanding', which all take their ordinary contextual meanings and which often overlap. There is no requirement to draw an artificial distinction between them by specifically identifying an 'arrangement' as one or the other. Rather, what is required for the operation of the section is that the nature and scope of the relevant 'agreement' be specified.[59]

68. While, for the purposes of section 100A, an agreement requires 2 or more parties[60], the agreement does not require:

- •

- an exact understanding of the parties to the nature and extent of the agreement and benefits to be provided and can, depending on the facts, be a plan comprising a series of steps undertaken individually by those parties over a period of time[61], or

- •

- the presently entitled beneficiary to be a party or even in existence when made[62], or

- •

- the relevant trust to be in existence when made.[63]

69. Consistent with the approaches of the Courts where the meaning of the words agreement, arrangement or understanding have been otherwise considered:

- •

- Where, as provided by subsection 100A(13), an agreement can be implied, it is open to infer that an agreement exists from the surrounding circumstances or the conduct of the parties.[64] In the particular context of section 100A, examples of where it is possible that this inference may be drawn include

- -

- where the conduct of the trustee and others is inconsistent with the rights and duties imposed by the trust deed and the general law

- -

- where parties act in accordance with the advice of a professional adviser (or rely on the professional adviser) in undertaking a series of steps or taking concerted action, in circumstances where the adviser has knowledge of the steps and their likely effects and/or the action and its intended purpose (whether or not the adviser is a party to the arrangement and whether or not all parties to the arrangement have this knowledge).

- •

- While an 'arrangement or understanding' must have been entered into consensually, the parties' acceptance or adoption may be tacit and it is not essential that they be committed or bound to support it. The arrangement may be both informal and unenforceable, and the parties may be free to withdraw from it or to act inconsistently with it, notwithstanding their adoption of it.[65] An arrangement or understanding may lack formality and precision.[66]

- •

- informal concerted action by which 2 or more parties may arrange their affairs towards a purpose[67]; an example in the particular context of section 100A would be an 'arrangement or understanding' that the beneficiary would act in accordance with the wishes of another person or group, or

- •

- an understanding that the parties will implement a series of steps undertaken individually or collectively by those parties over a period of time[68], or

- •

- the actual implementation of such a series of steps.

An entitlement that occurs in connection with or as a result of the reimbursement agreement

71. For subsection 100A(1) to apply, it must be the case that the present entitlement[69]:

... arose out of a reimbursement agreement or arose by reason of any act, transaction or circumstance that occurred in connection with, or as a result of, a reimbursement agreement ... .

72. These express terms describe the width of the provision, which extends beyond cases where there is a direct causal connection or relationship between the existence of the present entitlement and the reimbursement agreement. The equivalent extensions are made in subsection 100A(2) for cases about the payment to, or application for the benefit of, the beneficiary.[70]

73. It is sufficient for there to be a connection between the reimbursement agreement and some other act, transaction or circumstance from which the entitlement has arisen. If the beneficiary's present entitlement or the payment or application of income to or for them was one of the consequences of any act, transaction or circumstance that occurred in 'connection with' or 'as a result of' the reimbursement agreement, this aspect of subsections 100A(1) or (2) would be satisfied.[71] The existence of such a connection will depend on the facts of a particular case.

74. Where a present entitlement arises from an agreement or a payment or application of trust income results from an agreement, naturally, the relevant agreement must be in existence at the time when the present entitlement arises or the payment is made or funds applied.[72] However, the existence of that agreement might be established by evidence of the conduct of the parties before and after that time.[73]

75. Subsections 100A(5) and (6) complement subsections 100A(1) and (2), respectively, by deeming relevant trust amounts to have arisen out of or resulted from reimbursement agreements, without otherwise limiting the scope of the connection sufficient for section 100A to apply.[74] Specifically, where the amount by which a beneficiary's present entitlement (or an amount which is paid or applied for their benefit) (the increased amount) exceeds the amount the beneficiary would have been (or could reasonably be expected to have been) presently entitled to (or paid or applied for their benefit) absent either the reimbursement agreement or an act, transaction or circumstance that occurred in connection with, or as a result of, the reimbursement agreement (the original amount), that excess is taken to have arisen out of or resulted from the reimbursement agreement.

76. The taxpayer has the onus of establishing a reasonable expectation that the beneficiary would have been presently entitled to the original amount if the reimbursement agreement had not been entered into.[75] A 'reasonable expectation' requires more than a possibility. It involves a prediction as to events which would have taken place if the reimbursement agreement had not been entered into. The prediction must be sufficiently reliable for it to be regarded as 'reasonable'.[76]

Benefits to another requirement (subsections 100A(7), (11) and (12))

77. A reimbursement agreement must satisfy the conditions in subsection 100A(7). As observed by the courts, it is not necessary for there to be a reimbursement in the ordinary sense in order to satisfy the definition of reimbursement agreement.[77]

78. Subsection 100A(7) states that:

Subject to subsection (8), a reference in this section, in relation to a beneficiary of a trust estate, to a reimbursement agreement shall be read as a reference to an agreement, whether entered into before or after the commencement of this section, that provides for the payment of money or the transfer of property to, or the provision of services or other benefits for, a person or persons other than the beneficiary or the beneficiary and another person or persons.

79. Subsection 100A(7) does not limit who can be the provider of the money, property, services or other benefits. It also does not require that a benefit be provided directly.

80. Similarly, it is not a requirement of subsection 100A(7) that the 'relevant trust income', to which the beneficiary is presently entitled or has paid or applied for their benefit, also be the precise form or amount of the benefits that are provided to another person under the agreement. It is sufficient that someone other than the beneficiary benefits, such as by the provision of money, property, services or other benefits, whether directly or indirectly procured by (or in connection to or as result of) the beneficiary's present entitlement (or the income paid or applied for the beneficiary).

81. The reference to 'persons other than the presently entitled beneficiary' can be anyone, including the trustee[78], another beneficiary of the trust or any other person.

82. The meaning of 'payment of money' is extended by subsections 100A(10) and (12) to include a payment by way of loan and to the release, abandonment, failure to demand payment or postponement of payment of a debt. It follows that there is a payment of money where a beneficiary loans the amount of their entitlement to the trustee. The inclusion of the words 'or other benefits' means that condition could be satisfied in the case of an agreement where funds are not distributed but retained in the trust.

Tax reduction purpose requirement (subsection 100A(8))

83. Subsection 100A(8) excludes certain agreements from the definition of reimbursement agreement. It states:

A reference in subsection (7) to an agreement shall be read as not including a reference to an agreement that was not entered into for the purpose, or for purposes that included the purpose, of securing that a person who, if the agreement had not been entered into, would have been liable to pay income tax in respect of a year of income would not be liable to pay income tax in respect of that year of income or would be liable to pay less income tax in respect of that year of income than that person would have been liable to pay if the agreement had not been entered into.

84. An agreement is entered into for a tax reduction purpose if any of the parties to the agreement entered into the agreement for that purpose.[79] For there to be a tax reduction purpose, it is not necessary that an alternative postulate be established, so as to identify a specific amount of tax that would be avoided by an identified person[80], though such matters may be identifiable in many cases. In BBlood, Thawley J observed that[81]:

In the context of a discretionary trust for example, where a trustee has very broad discretions, it would often be difficult, if not impossible, to say with certainty what would have occurred were it not for the relevant agreement.

85. To meet the tax reduction purpose requirement:

- •

- the person whose tax liability is to be reduced or eliminated need not be a party to the reimbursement agreement[82]

- •

- the income tax liability to be reduced can be in relation to any year of income, meaning that a purpose of deferring tax to a later year would be sufficient to demonstrate the tax reduction purpose[83]

- •

- a person can have a purpose of securing a reduction in tax for subsection 100A(8) even where that purpose is not achieved[84] or ceases to be held at some time following the entry into the agreement

- •

- there is also no requirement that the tax reduction purpose be the sole or dominant purpose of the party or parties for entering into the agreement.[85] It need only be one of the purposes of the relevant party or parties for entering into the agreement.

86. While there is some structural similarity, the tax reduction purpose requirement in subsection 100A(8) is substantially different to the purpose requirement in the general anti-avoidance rule in section 260 which was operative when section 100A was enacted. Subsection 260(1) referred to a '... contract, agreement, or arrangement ... [that] has or purports to have the purpose or effect ... ' of avoiding tax in a described way. Subsection 100A(8) does not refer to the 'purpose or effect' of an agreement and instead refers to a purpose of one or more parties to the agreement.

87. The matters to be considered to determine purpose include the parties' own evidence as to their purposes for entering into the agreement and the objective facts and circumstances, including the financial, taxation and other consequences of the transactions entered into.[86]

88. The purpose of an adviser can be relevant in determining whether a tax reduction purpose exists. For example, the purpose of an adviser can be directly relevant if the adviser is party to the agreement or understanding to carry out the relevant steps in the transaction in accordance with their advice, as was found by the court in BBlood.[87]

89. Even where an adviser is not a party to the agreement or understanding, their purpose may, in certain cases, be imputed to another party to the agreement or understanding. This will occur if a party to the transaction acts in accordance with the adviser's advice (even if they are not aware of the adviser's purpose).[88]

Ordinary dealing exception (subsection 100A(13))

90. A further exception to the operation of section 100A is contained in subsection 100A(13):

agreement ... does not include an agreement, arrangement or understanding entered into in the course of ordinary family or commercial dealing.

91. The exception is satisfied where the relevant agreement is entered into in the course of ordinary family or commercial dealing. While it can be relevant to consider whether individual steps were entered into in the course of an ordinary family or commercial dealing, that is not the statutory test. It is the whole of the agreement, not those individual steps, that must be characterised as having been entered into in the course of ordinary family or commercial dealing.[89]

92. The definition of an agreement provides that it is the dealing 'in the course of' which the agreement is entered into that is tested.

93. The Oxford Dictionary defines dealing to refer to, relevantly, business relations, trading or conduct in relation to others.[90]

94. The dealing to be tested is identified by reference to the subject matter and terms of the agreement; that is, the transaction, set of transactions or other actions which implement and give effect to the agreement. For the exception to apply, it is this set of transactions or other actions which must be characterised as ordinary family or commercial dealing.[91]

95. Contextual facts and circumstances are also highly relevant. That context may assist to demonstrate the commercial and family objectives of an agreement. These may include, for example, the relationship or association between the parties and their economic or other relevant circumstances.

Example 1 - identifying family objectives

96. In an income year, family members agree to gift their trust distributions to one family member, Paul, who has significant medical bills. The arrangement is implemented via trust distributions to the family members and a gift by each of them to Paul. That Paul has significant medical bills is not a part of the agreement; however, it is a highly relevant contextual fact which demonstrates the content of the family objectives.

Ordinary family or commercial dealing - the core test

97. 'Ordinary family or commercial dealing' is a composite phrase. It is not defined for the purposes of section 100A and so takes its ordinary and legal meaning, having regard to statutory context.

98. The core test is that ordinary family or commercial dealing is explained by the family or commercial objectives that the dealing will achieve. The application of the test can involve an inquiry into what the objectives of the dealing are and whether the steps that comprise the dealing would achieve that objective. It can also be relevant to inquire whether the dealing or steps within the dealing might be explained instead by objectives different to those said to be behind the ordinary family or commercial dealing.[92] Illustrations can be found in case law:

- •

- In Prestige Motors, in concluding that the 3 transactions did not arise out of ordinary family or commercial dealing, the Court referred to the absence of commercial motivation or commercial necessity or justification for the transactions, and observed of one arrangement that the 'only explanation for the entry into the agreement ... [was] the elimination or reduction of tax liabilities'.[93]

- •

- In Guardian, the Court (Logan J) identified an agreement involving the incorporation of a company, the nomination of that company as an eligible beneficiary of a trust that conducted investment activities and the subsequent appointment of income from those investment activities to the company.[94] In concluding that the exception applied, the Court made findings on the evidence and posited that the identified agreement achieved the benefits of 'risk minimisation ... the shielding of distributed income and accumulated wealth from any creditors of individuals who were also members of the class of eligible beneficiaries' and the 'familial advantage ... of not having to make a large distribution in an income year to an individual'.[95]

- •

- In BBlood, in concluding the arrangement was not an agreement entered into in the course of ordinary family or commercial dealing, the Court observed that the arrangement was unusual, was more complex than was necessary to achieve any specific purpose that could be described as 'ordinary family or commercial dealing', and was neither explicable as being for family succession or for commercial purposes.[96] Further, the Court considered the arrangements in the context of the historical behaviour of the parties, concluding that it was inconsistent with that behaviour and that no sensible commercial or family rationale had been established for adopting the buy-back procedure.[97]

99. The method for applying the core test is to ask whether a dealing can be explained by, or is founded in, the achievement of family or commercial objectives. In one sense, this closely parallels the predication test in former section 260[98], first expressed in Newton[99] and applied in later High Court authorities on that section. Under the predication test, as originally formulated by Lord Denning on behalf of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, for the Commissioner to establish that an arrangement had the purpose or effect of avoiding tax, that purpose had to appear on the face of the arrangement. If having regard to the overt acts by which an arrangement was implemented, it was 'capable of explanation by reference to ordinary business of family dealing, without necessarily being labelled as a means to avoid tax', section 260 would not apply.

100. The Courts that have considered section 100A and observed that the wording of the ordinary family or commercial dealing test derives from the decision in Newton[100] have also cautioned that there are differences in the statutory tests as between sections 100A and 260.[101] Notwithstanding these differences, the principles drawn from the authorities[102] on former section 260 can be helpful in demonstrating whether family or commercial objectives explain, found or (to adapt the language of the section 260) cases are the predicate of the dealing to which the core test is being applied.

Family or commercial objectives

101. 'Family' in 'ordinary family or commercial dealing' takes its ordinary meaning. It refers to a relationship of natural persons based on birth or affinity, and may often involve co-residence. Family is not limited to any particular type of family relationship that is more common at a point in time than others.

102. For a dealing to be able to achieve commercial objectives, the parties would be expected to advance their respective interests. Transactions which would be normal or regular if seen in trade or commerce demonstrate that a dealing is founded in commercial objectives. A dealing can achieve commercial objectives, even in the absence of market value or where the parties do not deal at arm's length.

Commonplace transactions and intra-family transactions

103. What is commonplace is not the test. An arrangement that is commonplace, but which does not achieve family or commercial objectives, is not entered into in the course of ordinary family or commercial dealing.[103]

104. An agreement entered into between family members and the entities they control is not entered into in the course of ordinary family or commercial dealing where the dealing and the steps that comprise it do not have the quality of achieving any family or commercial objectives.

Factors which may point to an absence of ordinary family or commercial dealing

105. The core test involves an inquiry into what the objectives of the dealing are, whether the transactions achieve that objective and whether they are better explained by achieving some other objective. The test is applied on the facts of each case and to the whole of the dealing within which the agreement has been entered into 'in the course of'. In applying the test:

- •

- elements of contrivance or artificiality are factors which point against an agreement being entered into in the course of ordinary family or commercial dealing[104]

- •

- while complexity can be a necessary feature of transactions to achieve family or commercial objectives, an arrangement that is overly complex or lacking justification to achieve those objectives is a factor that will point against the agreement as having been entered into in the course of ordinary family or commercial dealing[105], and

- •

- the presence of other features which show that the arrangement is clearly tax-driven may also indicate that an arrangement is more properly explained by other objectives instead of family or commercial objectives.

Note: In Guardian, there are comments by the Court (Logan J) that the word 'ordinary' in ordinary family or commercial dealings 'is used in contradistinction to "extraordinary"'[106] and 'refers to a dealing which contains no element of artificiality'.[107] The Commissioner does not take his Honour to be saying that all dealings with no element of artificiality will necessarily be ordinary family or commercial dealings, nor that where there is some family or commercial feature to a dealing, it is only the factor of artificiality that could result in the exception not being met.

106. Instances which call for close examination to determine if one of the factors in paragraph 105 of this Ruling are present include those where:

- •

- the manner in which an arrangement is carried out has contrived or artificial features

- •

- family or commercial objectives could have been achieved more directly; for example, could the arrangement instead have simply or directly provided the benefit to the person who actually benefited, such as by making that person presently entitled to trust income

- •

- the complexity of the arrangement and the presence of additional steps that achieve no commercial purpose, and

- •

- the conduct of the arrangement is inconsistent with the legal and economic consequences of the beneficiary's entitlement (such as an asset or funds representing the entitlement are purportedly lent to others without any intention of being repaid).

107. Where income entitlements have actually been remitted to the beneficiary, amounts were subsequently returned or other benefits or services were provided, by way of gift or otherwise to another person (such as the trustee, another beneficiary or an associate, whether by the beneficiary or by the trustee either independently or under a power of attorney).

108. The inquiry to identify these factors does not substitute for the core test, which is to ask whether the dealing is explained by ordinary family or commercial objectives that it is likely to achieve. In this regard:

- •

- it has been recognised by the courts that complexity is a feature of many transactions that achieve commercial or family objectives[108]; as explained by the court in BBlood, where

... the agreement ... is overly complex, involving more than is needed to achieve the relevant objective, or includes additional steps which are not [seen as] necessary to achieving that objective, ... [that] ... the dealing might more readily be seen as not being "ordinary"

- •

- ordinary family and commercial objectives are commonly achieved in transactions which are chosen for the reason that they are tax effective when compared to similar alternatives to achieve those objectives.[109]

109. The test is objective. Cultural factors inform the question whether a dealing is to achieve family or commercial objectives.

Example 2 - cultural practice of gifting

110. Azra is a member of an extended family whose members' cultural values include grandparents gifting money or goods to younger members of the family during the festive season. This cultural practice is relevant in considering whether transactions that involve Azra gifting money to her grandchildren out of funds from a trust distribution she has received have been entered into in the course of ordinary family or commercial dealing.

Example 3 - cultural practice to support older relatives

111. Jack lives by the practices that have been common for centuries in the culture that he draws his heritage from. One of those practices is that children will meet the needs for shelter and living of their parents and other older relatives when they are no longer participating in the workforce. This is founded in notions of respect for elders and is practiced irrespective of what means those relatives would have to fund their own needs from available resources. This cultural practice is relevant in considering whether Jack's direction to the trustee of a trust to apply his entitlements to meet mortgage repayments for his aunt, who has retired from her employment working in a factory, is in the course of ordinary family or commercial dealing.

112. Cultural factors refer to the distinct and observable ideas, customs or practices of people or certain groups within a society. The existence of a cultural factor which is not widely understood in the broader community can be demonstrated by evidence. As the core test is applied to the whole of the agreement, rather than the individual steps, whether the presence of a cultural factor determines if a dealing is entered into in the course of ordinary family or commercial dealing will depend on the facts of the case.

Example 4 - cultural practice of not accepting entitlement

113. Max and the trustee of a trust he controls agree to distribute certain income of the trust to Asher, a non-resident who for religious reasons will not accept the entitlement. While Asher's beliefs are a cultural factor that explains why the entitlement will not be called for, in these circumstances they do not, without more, explain the objectives for making the resolution to distribute in the first place.

114. Section 100A is a specific anti-avoidance provision. While the application of other tax laws would be considered by parties entering into transactions which may have a family or commercial objective, whether those laws apply to a transaction is not a substitute or addition to the ordinary dealing exception. For example, the application of other provisions such as the income injection rules in Division 175 of the ITAA 1997 would not, in itself, prevent section 100A from applying.

Consequences - trustee liable for income tax and beneficiary relieved

115. The consequences of the application of section 100A are achieved by the statutory device of deeming. When section 100A applies:

- (1)

- ... the beneficiary shall, for the purposes of this Act, be deemed not to be, and never to have been, presently entitled to the relevant trust income ...

or

- (2)

- ... the relevant trust income shall, for the purposes of this Act, be deemed not to have been paid to, or applied for the benefit of, the beneficiary.

This has been described by the courts as 'switching off' the entitlement[110], which creates a statutory fiction.

116. Statutory fictions are generally to be read as not having an operation beyond that required to achieve their object or purpose[111], though other principles of statutory construction still apply.[112] They are not to be read more strictly than other provisions simply by reason of being a deeming provision.[113]

117. Here, the deeming required by section 100A is concerned with the relationship between the beneficiary and the 'relevant trust income'. In respect of subsection 100A(1), the section directs that 'for the purposes of this Act', the relationship denoted by the words 'present entitlement' is deemed not to exist and never to have existed.

118. The deeming in subsection 100A(1) creates a fictitious set of facts, consistent with that relationship having never existed, which are substituted for reality. An equivalent approach applies for subsection 100A(2), meaning that where:

- •

- subsection 100A(1) applies, the fictitious set of facts is that the beneficiary does not have, and never had, the rights or entitlements that would cause them to be presently entitled to the relevant income of the trust estate[114], and

- •

- subsection 100A(2) applies, the fictitious set of facts is that the beneficiary has not received a payment of that relevant income, and no amount has been applied for their benefit.[115]

119. The statutory fiction is stated to apply for the purposes of the Act.[116] In the context of section 100A, the deeming takes effect for purposes of the Act that operate to provide taxation consequences in relation to the entitlement which is the subject of section 100A.

120. The substitution of the fictitious set of facts does not extend to cause an entitlement to arise for another person (such as a default beneficiary) or to change the assets or balance sheet of the beneficiary for the purposes of the Act unrelated to the taxation of the entitlement. This limit on the scope of the statutory fiction promotes the legislative purpose of section 100A 'to bring about the result that trust income dealt with under reimbursement agreements would be taxed under section 99A'.[117]

Division 6 and related consequences

121. Any assessment of the net income of the trust estate to a beneficiary that would otherwise arise under section 97 will be proportionately reduced by the share of the income of the trust estate section 100A deems the beneficiary not to be presently entitled to or to have received or had applied for their benefit. Any part of the net income of the trust estate to the trustee that would otherwise have arisen under section 98 in respect of such a share would be likewise reduced, with section 98A then having no application in respect of that share.

122. The trustee is assessed and liable to pay tax on the relevant share of the net income of the trust under section 99A relating to so much of the income of the trust estate covered by the section 100A deeming, as section 100A has created the statutory fiction that no beneficiary is presently entitled to this part.

123. The deeming takes effect for those purposes of the Act that operate to provide taxation consequences in relation to the entitlement which is the subject of section 100A. However, for other purposes of the Act which are not about the taxation of trust net income flowing from the entitlement which was the subject of section 100A, the deeming does not operate to reduce or disregard the assets of the beneficiary.

124. For example, the deeming takes effect in the following ways:

- •

- No franking credits will arise for a corporate beneficiary in respect of tax otherwise payable in relation to an entitlement which has been switched off by the operation of section 100A.

- •

- No withholding tax liability will arise in respect of entitlements which would be subject to subsection 128A(3) in respect of a non-resident beneficiary, where the present entitlement is switched off by the operation of section 100A.

- •

- In the case of a corporate beneficiary, because the entitlement is taken not to arise, there will be taken to be no entitlement which could be the subject of a loan to the trustee under section 109D. Division 7A in those circumstances would not operate in respect of the entitlement.

125. In respect of the Division 7A interaction, the deeming achieves the statutory purpose of bringing an amount of trust net income to tax in the hands of the trustee at section 99A rates to the extent that the share of trust income to which the corporate beneficiary is presently entitled is the subject of the reimbursement agreement.

Capital gains and franked distributions

126. For 2010-11 and following income years, the allocation of capital gains and franked distributions that would have been included in the net income of a trust estate is no longer determined by Division 6. The allocation is determined instead by the application of specific rules in Subdivisions 115-C and 207-B of the ITAA 1997 (the streaming rules).[118]

127. The operation of the streaming rules to allocate trust capital gains and franked distributions is a purpose of the ITAA 1997 for which the deeming in section 100A applies. Where the terms of that section are satisfied for the facts of an arrangement, the streaming rules are applied to the fictitious set of facts deemed to exist rather than the actual facts.[119]

128. Whether and how this will have the result that the trustee will be liable to tax instead of a beneficiary will depend on the facts.

129. One way that a beneficiary includes an amount of a capital gain or franked distribution in assessable income is that they are 'specifically entitled', as they have received or can reasonably expect to receive a financial benefit referrable to the gain or distribution, in accordance with the terms of the trust.[120] The circumstance in which a beneficiary is specifically entitled will commonly involve actual or expected present entitlement to income of the trust comprising such a benefit, or the distribution of such income.[121] Where section 100A applies, the application of the law to a fictitious set of facts (where a payment does not happen or entitlement does not arise) may have the result that the beneficiary is taken not to be specifically entitled to an amount. As a result, the allocation of the gain or distribution will be made according to the parties' adjusted Division 6 percentages (as relevantly modified by the application of section 100A), within the meaning of the streaming rules.

Example 5 - allocation of capital gains when section 100A applies to a present entitlement

130. Trust income is defined to be equal to section 95 net income. The trustee derives the following income in the income year:

- •

- interest income of $10,000

- •

- non-discount capital gain of $30,000.

131. Beneficiary A is presently entitled to $5,000 trust income from interest. Beneficiary B is presently entitled to $5,000 trust income from interest and the capital gains. Beneficiary B's present entitlement confers the financial benefit which gives rise to a specific entitlement to the capital gain.

132. Beneficiary B's entitlements are subject to section 100A. Where Beneficiary B's total entitlements are subject to section 100A, the allocation will be as follows:

- •

- Beneficiary A is entitled to $5,000 trust income from interest

- •

- no one is presently or specifically entitled to $5,000 interest and $30,000 capital gain.

133. The capital gain is taxed in accordance with adjusted Division 6 percentages:

- •

- Beneficiary A's adjusted Division 6 percentage = [($5,000 ÷ $40,000) × 100] = 12.5%.

- •

- Trustee's adjusted Division 6 percentage = [($35,000 ÷ $40,000) × 100] = 87.5%

- •

- Beneficiary A is taxed on $5,000, which includes $3,750 (12.5% × $30,000) capital gain

- •

- Trustee is taxed on the balance of the capital gain which is $26,250 (87.5% × $30,000).

134. Another way that a beneficiary includes a capital gain or franked distribution is that no person is specifically entitled to an amount and the beneficiary includes a share[122] according to their adjusted Division 6 percentage.[123] Where section 100A applies, the application of the law to the fictitious set of facts will have the result that there is a decrease in the beneficiary's adjusted Division 6 percentage and an increase in the trustee's adjusted Division 6 percentage, within the meaning of the streaming rules.

Appendix 2 - Examples

This Appendix provides examples which illustrate the principles in the Ruling. Decisions on individual cases will depend on the overall circumstances of that case. Consequently, the conclusions reached in the following examples are not necessarily determinative of the Commissioner's views on cases with similar, but different, facts.

This Appendix provides examples which illustrate the principles in the Ruling. Decisions on individual cases will depend on the overall circumstances of that case. Consequently, the conclusions reached in the following examples are not necessarily determinative of the Commissioner's views on cases with similar, but different, facts.

|

Example 6 - trust established under a will

135. A trust established under a will provides that Taylor, the grandchild of the deceased, is entitled each year to all of the trust income, although it is not to be paid to them until they are 25 years of age (and thereafter) or, if they die before attaining the age of 25, to their estate.

136. At the time the trust is created, Taylor is 15 years of age. The income is used by the trustee to invest in further income-producing assets.

137. Section 100A does not apply to the entitlement to income of a minor beneficiary.[124] Additionally, after Taylor turns 18, section 100A would not apply to the retention of income until Taylor attains 25 years of age and the reinvestment of that income on the terms of the trust on these facts because:

- •

- even if further evidence were to show that this course of conduct involves an 'agreement' that would satisfy the connection requirement, it would be an agreement entered into in the course of ordinary family or commercial dealing

- •

- there is nothing in the stated facts to indicate that the tax reduction purpose would be satisfied.

Example 7 - distribution to spouses with mixed finances

138. The Rosegum Family Trust is controlled by spouses Lisa and Jessie Rosegum, who are the primary beneficiaries of the trust. The trust has a widely-drawn objects clause, which includes family members of Lisa and Jessie and their related entities.

139. Each year, the trust makes Lisa and Jessie presently entitled to the income of the trust in equal proportions.

140. Lisa and Jessie have generally shared financial responsibilities and fund their lifestyle from a common pool of assets, save for some expenses which they fund from their own savings individually, such as expenses incurred by Jessie for their hobby garden.

141. While the facts do not indicate whether any person had a purpose of reducing income tax when entering into the agreement, so as to cause the tax reduction purpose requirement to be satisfied, the arrangement is nonetheless unlikely to be a reimbursement agreement.

142. Trust distributions to spouses who generally have shared financial responsibilities and who ultimately enjoy the shared benefits of the distribution would usually be capable of explanation as achieving ordinary family objectives. On these facts, the organisation of financial affairs between spouses would likely be entered into in the course of ordinary family or commercial dealing.

Example 8 - gift from parents to a child

143. Assume the same facts as Example 7 of this Ruling. In one year, Alex (being Lisa's eldest daughter and Jessie's stepchild) purchases a property. Lisa and Jessie pay for the deposit for the purchase of the home as a gift to Alex, from funds attributable to their distribution from the Rosegum Family Trust. While on these facts, the creation of an entitlement and gifting from that entitlement may raise questions about whether the entitlement arose under or in connection with an agreement between the parties, the making of gifts between family members for ordinary family objectives, such as parents contributing to the purchase of a house, would usually be ordinary family or commercial dealing.

144. The following additional or alternative facts may change the conclusion made in paragraph 143 of this Ruling and make it less likely that an agreement has been entered into in the course of ordinary family or commercial dealing. Were that the case, it would be of greater relevance to examine whether one or more persons have a purpose of reducing income tax when entering the agreement (so as to cause the tax reduction purpose requirement to be met) and examine further whether the connection requirement is met:

- •

- If the arrangements were to involve parents gifting money received from a trust to their children repeatedly and one or more of the following factors are present

- -

- the parents have a lower marginal tax rate

- -

- the parents have lesser financial means than the adult child, or

- -

- the adult child is also capable of benefitting under that trust in their own right; for example, the parents may be subject to lower tax rates because they are retired and in pension phase or have significant losses to reduce tax payable on trust distributions.

- •

- Arrangements where the situation is reversed, so that Alex (who has limited financial resources apart from a distribution made to her and has a lower marginal tax rate) gifts money to her parents Lisa and Jessie who are subject to higher rates of tax, and there is no financial or cultural circumstance that would explain the gift.

- •

- Arrangements where Alex, who has a lower marginal tax rate, agrees to apply her trust entitlements to reimburse her parents for costs incurred by them on her maintenance, education and financial support while Alex was a minor.

Example 9 - unpaid entitlements held on trust